Главная страница Случайная страница

Разделы сайта

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

St. Burlesque, Circus, Clowns, and Acrobats

|

|

(pages 289-305)

[289]

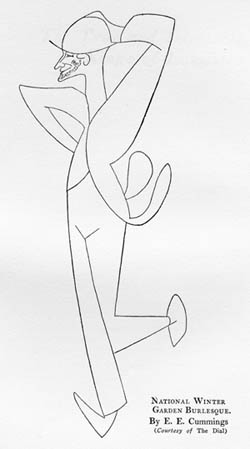

THIS is a footnote in the interest of justice more than anything else. The general scheme of this book is that it is to be an outline, for each of its major chapters is devoted to a subject about which a book ought to be written-but not by me. In such an outline there is no specified allotment of space, and I have written most on the lively arts in which I myself take the liveliest pleasure. Burlesque is not of these-and I confess to enjoying it most in the person of those artists who come out of it into revue, or vaudeville, or any other framework with which I am familiar and which I admire. I can understand an enthusiast feeling the same way about them as I feel about revue and vaudeville players who try to enter the legitimate stage that they are corrupted by a desire to be refined. The great virtues of burlesque as I (insufficiently) know it are its complete lack of sentimentality in the treatment of emotion and its treatment of appearance. The harsh ugliness of the usual burlesque make-up is interesting- I have seen sinister, even macabre, figures upon its stage-and the dancing, which has no social refinement, occasionally develops angular positions and lines of exciting effect. I find the better part of burlesque elsewhere, notably in clowns. And instead of trying to be fair to a medium I do not know well, nor care too much about, I have put in a picture which I greatly

[291]

admire and which probably is more to the point than anything I could write. I shall try to find a picture for the circus, too. Because the circus is a mixed matter and some of it is superb. The jeux icariens I have never seen except in France: they are really exquisite. They are usually performed by a whole family. The training is exceedingly arduous, must be begun in childhood, and the art is dying out. In this act the essential thing is the use of human bodies as maniable material. The small boy I saw rolled himself into a tight round ball and was caught on the upturned feet of his father, flat on his back, and tossed to another grownup in the same position, the little rolled-up body spinning like a ball through the air. The beauty of the movements, the accuracy and the finesse of the exploitation of energy, delighted. Trained elephants, however, haven't exactly this quality; and trained seals, agreeable to watch because they are graceful and supple of body, lack something. I have seen a diabolo player who was beautiful to follow, and a juggler who placed two billiard cues end to end on his forehead, threw a ball and caught it at the top of the cues, then dislodged the ball and put it into play with three others. This extraordinary mixture of good and dull things, this lack of character, makes the circus easy to like and useless to think about. The special atmosphere of the circus, the sounds and sights, and smells, are, of course, another matter.

[292]

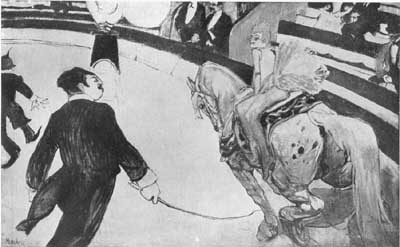

Cirque Medrano. By Henri Toulouse-Lautrec

Two of its actual features justify speculation: acrobats and clowns. The American vaudeville player can say nothing worse of an audience than " they like the acrobats. " When they hang by their teeth I cannot respect them; the development of any part of the human body is interesting, no doubt, and I do not wish to insist that there must be an aesthetic interest in every act. But I feel about them as the Chinese philosopher felt about horse-racing: that it is a well-established fact that one horse can beat another, and the proof is superfluous. But there are trapeze workers whose technique is a joy to see and who exploit all the possible turns, leaps, somersaults in air, so that one is pleased and dazzled. I do not wonder that painters in every age have found them lovely subject. But a lady balanced on one leg of trapeze bar, smoking a cigarette, fanning herself, not holding on to anything-means exactly nothing to me unless it is accomplished with some other quality than nerve. I am sure she will never fall and do not care to be present when she does.

Clowns are different. Even those poor nameless ones who dash in between major acts and with noise and toy balloons divert little children, have some quality. They partake of our tradition about masks, they can't help having background. Everything exaggerated and ugly in burlesque is here put to the uses of laughter; even the dullest has some gaiety in make-up, in a mechanical contrivance, ingait or ges-

[293]

ture. Marceline helping the attendants with Powers' Elephants at the Hippodrome, so busy, so in the way, so unconscious of hindering, always created a little world around himself. Grock is incredible in the faultlessness of his method; as musical-eccentric he surpasses all other clowns, and his simple attitude before chairs and pianos and the other complications of life is a study in creativeness. I have written elsewhere of Fortunello and Cirillino, also great clowns; and they complete this sketchy footnote, since for the greatest clowns I have ever seen, nothing short of a separate title will suffice.' I A footnote to a footnote is preposterous. Perhaps the very excess of its obscurity will give it prominence and render faint justice to the old NewYork Hippodrome. It is a fine example of handling of material, and of adjustment, spoiled occasionally by too much very loud singing and a bit of art. It is part of New York's small-townness; but it is so vast in its proportions that it can never acquire the personal following of a small one-ring circus like the Medrano in Paris. I adore the Hippodrome when it is a succession of acts: the trained crow and Ferry who plays music on a fence and the amazing mechanical and electrical effects. Joe Jackson, one of the greatest of clowns, played there, too, and had ample scope. I like also the complete annihilation of personality in the chorus. When you see three hundred girls doing the same thing it becomes a problem in mass-I recall one instance when it was a mass of white backs with black lines indicating the probable existence of clothes-the whole thing was quite unhuman. And one great scene in which, I believe, the whole of the personnel participated: there were, it seemed, hundreds of tumblers and scores of clowns, and a whole toyshop in excited action. Oddly enough, one finds that the weakness the Hipis in its humour; there is plenty of it, but it is not concentrated, and there is no specific Hippodrome " style." What it will become under the new Keith rigime remains to be seen.

[294]

NATIONAL WINTERGARDEN BURLESQUE.

By E. E. Cummings(Courtesy of The Dial)

THE TRUE AND INIMITABLE KINGS OF LAUGHTER

[297]

CLOWNs are the most traditional of all entertainers and one of the most persistent of the traditions about the miss that those who have just died were better than those one has laughed at a moment ago. A very obvious reason is that the clowns of the recent past are the clowns of our own childhood. It is my fortunate position never to have seen a clown when I was a child, and all those I have ever laughed at are alive and funny. One of them, the superb Grock, was a failure in New York; the remarkable Fortunello and Cirillino who arrived with the Greenwich Village Follies of1922 are acrobats of an exceptional delicacy and humour; there isn't a touch of obvious refinement about them andthey are exquisite. And the real thing in knockabout grotesquerie are the three who call themselves, justifiably, the true and inimitable kings of laughter, the brothers Fratellini at the Cirque Medrano in Paris.

The Cirque Medrano is a one-ring circus in a permanent building near the Place Pigalle; ten times a week it fills the vast saucer of its seating capacity at an absurdly low price-the most expensive seats, I believe, are six francs-and presents something a little above the average European circus bill. There are more riding and a few more stunts than at others, and there are less trained animals. And ten times weekly the entire audience shouts with gratification as Francesco Fratellini steps gracefully over the ring,

[295]

hesitates, retreats, and finally sits down in a ringside seat and begins a conversation with the lady sit- ting beside him. Fratellini and makes them great is a sort of internal logic in everything they do. When the spangled figure with the white- washed face sits down by the ring and chats a moment it is Merelyn ARACD disconcerting; at once the logic appears-he is waiting for the show to begin. An attendant approaches and tells him to stop stalling, that the peopleare waiting to be amused. He replies in an odd English that he has paid his " mawney" and why doesn't the show begin.

Promptly another attendant repeats the message of the firstin English; Francesco replies in Italian. By the time theprocess has been gone through in five languages the clown has changed his tack entirely; you realize that since hedoesn't understand what all these uniformed attendants aresaying to him, he thinks that they are the show and he istrying to conceal his own irritation at being made the object

[298]

of their addresses and at the same time he is pretending tobe amused at their antics. The last time he speaks in whatseems to be gibberish (it is credibly reported to he rather fair Turkish) and the attendants fall back. From theopposite entrance to the ring arrives a figureof unparalleled grotesqueness-garments vast and loose in unexpected places, monstrous shoes, squares like windowpanes over his eyes, a glowing and preposterous nose. His gait is of theutmost dignity, he senses the sit-uation and advances to Frances-co's seat; and as a pure matterof business he delivers a terrificslap, bows nobly, and departs. Alan-w At Francesco enters the ring. the same time a third figureappears-a bald-headed man in carefully arranged clothes, amonocle, and a high hat, a stick. The three Fratellini are onthe scene (1). It is impossible to say what happens there, for theFratellini have an inexhaustible repertoire. The materialsare always of the simplest, and the effects, too; they havehardly any " props, " the costumes, the smiles, themovements, the gestures, are almost exactly alike from dayto day. Much of their material

(1) I have seen them since in another entrance, the most brilliant of all. SeeAppendix.

[299]

is old, for they are the sons and grandsons of clowns as farback as their family memory can carry; I have seen themonce appear armed for a fight with inflated bladders, looking precisely like contemporary pictures in MauriceSand's book about the commedia dell'arte, and on anotheroccasion have seen them so carried away with the frenzy oftheir activity that they actually improvised and proved theirdescent from this ancient form. They do burlesquesketches-a barber shop, a bull fight, a human elephant, amagician, or a billiard game; the moment they stop the entire audience roars for " la musique, " the most famous oftheir acts, remarkable because it has a minimum ofphysical violence.

La Musique is all a matter of construction and is awonderful example of the use of material. For at bottom itconsists of the efforts of two men to play a serenade andthe continual intrusion of a third. Francesco and Paoloarrive, each carrying a guitar or a mandoline, and place twochairs close together exactly in the centre of the ring. They step on the chairs and prepare to sit on the backs9 but eventhis simple process is difficult for them, as neither iswilling to sit down before the other, nor to remain seatedwhile the other is still erect, and they must be continuallyrising and apologizing until one flings the other down andkeeps him there until he himself is seated. Ready then, theyblow out the electric lights and strike the first notes; but the spotlight deserts

[300]

them; they are left in the dark and puzzled; they regard oneanother with dismay and suspicion. Suddenly they see itacross the ring and, descending with great gravity, carry their chairs across. Again they start, and again the spotlightgoes; their irritation mounts, but their dignity remains andthey follow it. It flits back to where they had come from.

There is a consultation and the two chairs are returned totheir original place in the centre of the ring. Then the two musicians take off their coats, prowl around the ringstalking the light, and fall upon it; then slowly and withmuch labour they lift the light by its edges and carefullycarry it back to their chairs. And as they begin to play thegrotesque marches in behind them, unconscious of them, intent only upon his vast horn and the enormous musicalscore he carries. Unseeing and unseen, he prepares himself, and at about the tenth bar the great bray of his horn shattersthe melody of the strings. The two musicians are dismayed, but as they cannot see the source of the disturbance, theytry again; again the horn intrudes. This time there isexpostulation and argument with the grotesque, but, as hereasonably points out, music was desired and he is doinghis share. There is only one issue for such a scene, and ittakes place, in a riot.

The preparation of these riots is a work of real delicacy, for the Fratellini know that two things are equally true: violence is funny and violence ceases to be funny.

Like Chaplin, they infuse into their

[301]

violence the sense of reason-they are violent only when noother means will suffice. In the photographer scene theycall into action the " august" a stock character of theEuropean circus, played at the Medrano with exceptionalskill by M Lucien Godart. The august is a man of greatdignity whose office it is to parley with clowns, be the buttof their jokes, and in M Godart's version, set off theirgrotesque appearance by an excellent figure and the mostcorrect of evening clothes. (He is in addition a rather goodtumbler, and it is part of the Medrano tradition for theaudience to hiss him until he grows seemingly furious andturns twenty difficult somersaults around the ring.) TheFratellini, armed with a huge black box and a cloth, ask himto sit for his photograph. Francesco takes it upon himself toexplain the apparatus, Paolo standing close by with thethree fence posts which represent the tripod, and Alberto, the grotesque waiting near by. Suddenly the tripod falls onAlberto's feet and he howls with pain; Paolo picks the postsup again, and again they fall, and again he howls. It is unbelievable that this should be funny, yet it is funnybeyond any capacity to describe it for one reason which thespectator senses long before he sees it. That is that thetripod is not intentionally thrown on the feet of thegrotesque. The fault is Francesco's, for he is explaining themachine and making serious errors, and every time hemakes a mistake Paolo gets excited and forgets that he hasthe

[302]

tripod in his hand, and simply lets it drop. One senses hisacute regret, and at the next moment one realizes that hisscientific zeal, his respect for his profession ofphotographer, simply does not permit him to let amisstatement pass; his gesture as he turns to set the matterright is so eager, so agonized, that one doesn't see what hashappened to the tripod until it has fallen. And to point themoral of the matter, when the grotesque Alberto after thefifth time picks the tripod up and attempts to slay Paolo, Paolo is again turning toward the others and the blow goes wide.

What the Fratellini are doing here is, to be sure, whatevery great actor does-they are presenting their effectsindirectly. The difficulty for them is that in the end theymust give their effects with the maximum of directness-they have to strike a man in the face and make the soundtell. In the scene of the photograph the august is " he who gets slapped" (the phrase is a common one) and the sceneis carefully built up through his reluctance and stupidity inposing. At first it is only an exaggeration of the customarydifficulties between a photographer and a little child; but asthe august becomes more and more suspicious of theintentions of the photographer, the clowns become moreand more insistent that he, and nobody but he, shall havehis picture taken. Gradually an atmosphere of hostility isbuilt up; the august tries to escape from the ring and ishauled back; then

[303]

dragged, then forced to sit; the opposing wills grow more and more violent; the audience senses the good will of the clowns, the obstinacy of the august; not a push or shove is given without reason and meaning. And when they see that there is nothing else for it, the three hurl themselves upon the clown in a frenzy of destructiveness and he is rent limb from limb. (In actual fact only his exquisite evening clothes were rent, but the effect is the same.)In these scenes and almost all their others, the Fratellini escape the reproach of being nothing but violent, while they hold every good element which violence in action can give them. To them are comparable the best (and only the best)of Eddie Cantor's scenes-when he applied for the job of policeman and when he was examined for the army-where there is a play of motive and a hidden logic. In their world everything must be sensible, and the most sensible thing in the world is to hit out. Behind them is a dual tradition-centuries of laughter and centuries of refining the instruments by which simple laughter can be produced. For it is opposed to their sense of fitness (as it is to ours) that the clown should create an effect of subtlety.' The kind of laughter they produce must involve the whole body, but not the mind. They have to be active all the time, so that you are dazzled and cannot think; and they must 'They nevertheless played exquisitely, I am told, in the Cocteau Milhaud Boeuf sur le Toit.

[304]

shake the solid ground under your feet, so that you may shake with laughter. What the critical observer discovers as method must reach the - actual average spectator only as effect. All of this the Fratellini have accomplished- " these three brothers who constitute one artist" are the complete exemplars of their art. Seeing them week, and nearly two dozen times sometimes twice an I find their actualities inexhaustible. Even in the descriptions noted above it can be seen that they have a definite sense of pace; their changes from fast to slow in the middle of an act, their variations from violence to trickery, their complete mastery of climax, their fertility of invention, are all elements of superiority. But they are only elements in a composition based on something fundamentally right-the knowledge that we have almost forgotten how to laugh in the actual world, and that to make us laugh again they must create a world of their own.

[305]

The Great God Bogus

(pages 306-319)

[306]

THE GREAT GOD BOGUS

IF there were an Academy I should nail upon its doors the following beliefs:

That Al Jolson is more interesting to the intelligent mind than John Barrymore and Fanny Brice than Ethel;

That Ring Lardner and Mr Dooley in their best work are More entertaining and more important than James B. Cabell and Joseph Hergesheimer in their best;

That the daily comic strip of George Herriman (Krazy Kat) is easily the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America to-day;

That Florenz Ziegfeld is a better producer than David Belasco;

That one film by Mack Sennett or Charlie Chaplin is worth the entire auvre of Cecil de Miller

That Alexander's Ragtime Band and I Love a Piano are musically and emotionally sounder pieces of work than Indian Love Lyrics and The Rosary;

That the circus can be and often is more artistic than the Metropolitan Opera House in New York;

That Irene Castle is worth all the pseudo-classic dancing ever seen on the American stage; and

That the civic masque is not perceptibly superior to the Elks' Parade in Atlantic City.

[309]

Only about half of these are heresies, and I am quite ready to stand by them as I would stand by my opinion of Dean Swift or Picasso or Henry James or James Joyce or Johann Sebastian Bach. But I recognize that they are expressions of personal preference, and possibly valueless unless related to some general principles. It appears that what I care for in the catalogue above falls in the field of the lively arts; and that the things to which I compare them (for emphasis, not for measurement) are either second-rate instances of the major arts or first-rate examples of the peculiarly disagreeable thing for which I find no other name than the bogus. I shall arrive presently at the general principles of the lively arts and their relation to the major. The bogus is a lion in the path.

Bogus is counterfeit and counterfeit is bad money and bad money is better-or at least more effective than good money. This is not a private paradox, but a plain statement of a law in economics (Gresham's, I think) that unless it is discovered, bad money will drive out good. Another characteristic of counterfeit is that, once we have accepted it, we try to pass it off on some one else; banks and critics are the only institutions which don't-or ought not to-continue the circulation. In the arts counterfeit is known as faux bon-the apparently good, essentially bad, which is the enemy of the good. The existence of the bogus is not a serious threat against the great arts, for they

[310]

have an obstinate vitality and in the end-but only in the end-they prevail. It is the lively arts which are continually jeopardized by the bogus, and it is for their sake that I should like to see the bogus go sullenly down into oblivion.

Namely: vocal concerts, pseudo-classic dancing, the serious intellectual drama, the civic masque, the high-toned moving picture, and grand opera.

The first thing about them is that a very small percentage of those who make the bogus arts prosperous really enjoy them. I recall my own complete stultification after hearing my first concert; and the casual way in which I made it evident to all my companions that I had been to a concert is my only clue to the mystery. For at bottom there is a vast snobbery of the 'intellect which repays the deadly hours of boredom we spend in the pursuit of art. We are the inheritors of a tradition that what is worth while must be dull; and as often as not we invert the maxim and pretend that what is dull is higher in quality, more serious, (" greater art" in short than whatever is light and easy and gay. We suffer fools gladly if we can pretend they are mystics. And the fact that audiences at concerts and opera, spectators at classic dances and masques, are suffering, is the final damnation, for it means that these arts are failures. I do not found my belief on any theory that all the arts ought to be appreciated by all the people. I do mean that most of those who read Ulysses or The Pickwick

[311]

Papers do so because they enjoy it, and they stop the moment they are bored. There is no superiority in having read a book. The lively anticipation of delights which one senses in those going to the Follies or to a circus is wholly absent in the lobby of the Metropolitan or at a performance of Jane Clegg. And the art which communicates no ecstasy but that of snobbism is irretrievably bogus.

There is something hopeless about opera as we know it in the United States; and the fact that ten or fifteen operas are among the permanent delights of civilized existence does not alter the fact. (Three of them: Chovanstchina, The Marriage of Figaro, and Don Giovanni, are not in the repertoire of the Metropolitan; nor are Falstaff and Otello; nor does the ballet proceed beyond Coq d'Or; nor it seems would the Metropolitan hold it within its dignity to produce The Mikado, although Schumann-Heink was ready to sing Katisha.) Here is an art-form hundreds of years old, prospered by an enormous publicity, favoured by extraordinary windfalls-the voice of Caruso, the " personality" of Farrar-able to set into motion nearly every appeal to the senses in colour, tone, movement -it has song and action and dance-and what exactly is the final accomplishment? The pale maunderings of Puccini, the vulgarity of Massenet, and the overpowering dulness of our domestic try-outs. Wag ner? A philosopher drunk with divine wisdom is reported (by Goethe) to have cried out that he could

[312]

discern shortcomings even in God; and the melancholy truth is that the welding of three arts into one succeeded only in Wagner's brain, for on the boards we lose Wagner as we attend to the stage, and regain him as we return to the music. This is not true of Boris or of Figaro-so much less pretentious, both; and the director may arise who will know how to fuse Wagner into one harmonious and beautiful object.

At the moment, one takes the Metropolitan with its vast seating capacity, its endless sources of appeal to the multitude, and one knows that it isn't a success. If it isn't losing money it is paying its way through social subventions. Eighty per cent of the music heard there is trivial in comparison with either good jazz or good symphonic music; ninety per cent of the acting is preposterous; and the settings, Costumes, and properties are so far below popular musical comedy standards that in the end Urban and Norman-Bel Geddes have had to be called in to save them, and haven't been given scope or freedom enough to succeed. The Metropolitan is, I am told, the finest opera house in the world and loses money because it is still several leaps ahead of its clientele which insists on more Puccini and no Coq d'Or. Also I have had the supreme pleasure of hearing Chaliapin there and I am not ungrateful. The Metropolitan has difficulties happily unknown to us and is unquestionably an eminent institution. It is opera as we know it, that calls down the curse, opera which has

[313]

to call itself " grand" to distinguish itself from the popular, superior, kind. For it is pretentious and it appeals not to our sensibilities but to our snobbery. It neither excites nor exalts; it does not amuse. Over it and under it and through it runs the element of fake; it is a substitute for symphonic music and an easy expiatory offering for ragtime. Ecrasez Pinfdme!

Audiences at the opera have, however, been thrilled bv a voice. What is there to say for the uncommunicative, uninspired, serious-minded intellectual drama which without wit, or intensity, " presents a problem" or drearily holds the mirror up to nature! Those little scenes from domestic life, those secondhand expositions of other people's philosophies, those unflinching grapplings with " the vital facts of existence" which year by year are held to be great plays? Let me be frank; let me face my vital facts. I have never found my brain inadequate to grapple with their grapplings, for it is almost in the nature of the case that if a man has anything profound to express he will flee from the theatre where everything is dependent upon actors usually unintelligent and is reduced to the lowest common factor of human intelligence. Bernard Shaw writes his ideas into his prefaces because they can't be fully stated on the stage; Henry James tried to be delicate and failed. It remains for Ferencz Molnar and Augustus Thomas to succeed-with borrowed and diminished ideas.

[314]

Still speaking of modern serious plays (because the Medea of Euripides and the tragedy of Othello are not involved) what is bogus in them is their spurious appeal to our sentimentality or our snobbery. It is their pretence to be a great and serious art when they are simply vulgarizations. I have no quarrel with any man for the subject matter of his work of art, and I should allow every freedom to the artist. The whole trouble with our modern serious drama is that it is usually such bad drama; the tedium of three hours of Jane Clegg isn't worthy sitting through because of the desperate effort of the dramatist and the producer to create the illusion of reality by reproducing the rhythm of reality. The essential distortion, caricature, or transposition which you find in a serious work'of art or in a vaudeville sketch, is missing here. And the efforts to ram this sort of play home by pretending that only morons do not like it is exactly and precisely bunk. Most plays fail because they are bad plays; and the greater part of the intellectual drama following this divine LAW, fails. A good manipulator of the theatre like Molnar can put over Lillom, which has no more of a great idea than Seven Keys to Baldpate and is almost as good drama, if he knows in what proportion to mingle his approaches to our meaner and higher sensibilities. For we are not altogether lost yet.

If the civic masque and classic dancing continue much longer we will be lost entirely. These arty

[315]

conglomerations of middle-high seriousness and bourgeois beauty are not so much a peril as a nuisance. The former is the " artistic" counterpart of the Elks Parade and since I cannot speak with decent calm about its draperies and mummery, I recommend Mr R. C. Benchley's chapter on the same subject in Of All Things! The civic masque is fake medivalism, the sort of thing which, if ridicule could kill, should

have gone out after W. S. Gilbert's couplets appeared in Patience. Alas the instinct for trumpery art persists and on it has been grafted the astounding idea of communal artistic effort-a characteristic thing, too, for the communal efforts of ancient Greece were war and Bacchanalia, and of the middle ages, the crusades; the municipal celebrations after which the civic masque is patterned were created in cities which were unself-conscious and were doing something out of vanity and joy. I cannot imagine the six million of New York or the six thousand of Vine land, Arkansas, growing suddenly mad with joy over the fact that they live in no mean city. I neither like the civic consciousness nor believe deeply in its honest existence. And when it takes to expressing itself as the symbol of the corn and such-like idiocy it isn't as funny as the induction scene of the Ziegfeld Follies (which the Forty-niners took off as " I am the spirit of Public School Number 146") and it isn't any more moving or intelligent. Certainly it has never been so beautiful. Faced with the vast

[316]

myths of the American pasts, our poets simply haven't found the medium for projecting them. The dime novel and the Wild West film both failed for

of imaginative power, and that treasure remains undisturbed. It is sealed and guarded and the civic masque nibbles at it, dislodges a fragment, and comes dancing awkwardly into the foreground waving the shadow of an illusion like a scarf over its head.

For obviously classic dancing is the natural form of expression for this pseudo-civism. I have never had the patience to discover the beginnings of the fatuous craze for imitations of presumably ancient dances. Certainly the first of the notable dancers I saw was not before 1907-in the person of Isadora Duncan. It would be absurd to recall those renditions of the Seventh Symphony and what not at this date. If Miss Duncan is a great artist and a great personality now, so much the better, for her early success had much to do with breaking down the gates of our decent objection to fake and her imitators swept over us like a flood. Bogus again, these things; they interpret in dance things which had already been all too clear in music or drama. They know, it seems, the science of eurhythmics, which ought to mean good rhythm, and they employ it to produce in pantomime an obvious, brutally flat version of the Fall of Troy. They haven't as yet added one single thing to our stock of interest and beauty-as the Russian Ballet did, as the old five-position ballet

[317]

dance did, as modern ballroom and stage dancing does. The costuming is almost always silly; the music chosen is almost always obvious; and the postures assumed are lethally monotonous. The old ballet, based on five definite positions, made each slight variation count, and Pavlowa with her stricken face and tenderness of movement knew it by heart, or by instinct. The new dancers have no internal discipline and no freedom; and only the accident that the human body is at times not displeasing to look upon makes them tolerable. One could forgive them much if the pretensions were not so unutterably lofty and the swank so ignorant and the results so ugly. Fat women leaping with chaplets in their hair, in garments of grey gauze, are not the poetry of motion, and Irene Castle in a black evening dress dancing Irving Berlin's music is-just as surely as Nijinsky was. What is more, these two dancers, whom I choose at the extremes of the dance, both have reference to our contemporary life; and the classic dancing of Helen Moeller and Marion Morgan and Mr Chalif and the rest have absolutely nothing to say to us. We've lost that " simplicity, " thank God, or haven't found it yet. We are an alert and lively people-and our dance must actually express that spirit as no fake can do.

Our existence is hard, precise, high spirited. There is no nourishment for us in the milk-and-water diet of the bogus arts, and all they accomplish is a genteel

[318]

corruption, a further thinning out of the blood, a little extra refinement. They are, intellectually, the exact equivalent of a high-toned lady, an elegant dinner or a refined collation served in the saloon, and the contemporary form of the vapours. Everything about them is supposed to be " good taste, " including the kiss on the brow which miraculously, cc ruins) I a perfect virgin-and they are in the physical sense of the word utterly tasteless. The great arts and the lively arts have their sources in strength or in gaiety-and the difference between them is not the degree of intensity, but the degree of intellect. But the bogus arts spring from longing and weakness and depression! A happy people creates folk songs or whistles rag; it does not commit the vast atrocity of a " community sing-song"; it goes to Olympic games or to a race track, to Iphigenza or to Charlie Chaplin-not to hear a " vocal concert."

The bogus arts are corrupting the lively onesbecause an essential defect of the bogus is that they pretend to be better than the popular arts, yet they want desperately to be popular. They borrow and spoil what is good; they persuade people by appealing to their snobbery that they are the real thing. And as the audience watches these arts in action the comforting illusion creeps over them that at last they have achieved art. But they are really watching the Quanto pili, un' arte Porta seco fatica di corpo, tanto pil a vilet Pater, who quotes this of Leonardo, calls it " princely."

[319]

An Open Letter to the Movie Magnates

(pages 320-343)

Manifestations of the Great God Bogus-and what annoys me most is that they might at that very moment be hailing Apollo or Dionysos, or be themselves participating in some of the minor rites of the Great God Pan.

[320]

An Open Letter to the Movie Magnates

AN OPEN LETTER TO THE MOVIE

MAGNATES

IGNORANT AND UNHAPPY PEOPLE:

The Lord has brought you into a narrow placewhat you would call a tight corner-and you are beginning to feel the pressure. A voice is heard in the land saying that your day is over. The name of the voice is Radio, broadcasting nightly to announce that the unequal struggle between the tired washerwoman and the captions written by or for Mr Griffith is ended. It is easier to listen than to read. And it is long since you have given us anything significant to see.

You may say that radio will ruin the movies no more than the movies ruined the theatre. The difference is that your foundation is insecure: you are monstrously over-capitalized and monstrously undereducated; the one thing you cannot stand is a series of lean years. You have to keep on going because you have from the beginning considered the pictures as a business, not as an entertainment. Perhaps in your desperate straits you will for the first time try to think about the movie, to see it steadily and see it whole.

My suggestion to you is that you engage a number of men and women: an archaeologist to unearth the history of the moving picture; a mechanical genius to explain the camera and the projector to you; a typical movie fan, if you can find one; and above all

[323]

a man of no practical capacity whatever: a theorist. Let these people get to work for you; do what they tell you to do. You will hardly lose more money than in any other case.

If the historian tells you that the pictures you produced in igio were better than those you now lose money on, he is worthless to you. But if he fails to tell you that the pictures of igio pointed the way to the real right thing and that you have since departed from that way, discharge him as a fool. For that is exactly what has occurred. In your beginnings you were on the right track; I believe that in those days you still looked at the screen.

Ten years later you were too busy looking at, or after, your bank account. Remember that ten years ago there wasn't a great name in the movies. And then, thinking of your present plight, recall that you deliberately introduced great names and chose Sir Gilbert Parker, Rupert Hughes, and Mrs Elinor Glvn. If I may qu'ote an author you haven't filmed, it s~all not be forgiven you.

Your historian ought to tell you that the moving picture came into being as the result of a series of mechanical developments; your technician will add the details about the camera and projector. From both you will learn that you are dealing with move ment governed by light. It will be news to you.You seem not to realize the simplest thing about your business. Further, you will learn that everything

[324]

YOU need to do must be by these two agencies: movement and light. (Counting in movement everything f pace and in light everything which light can make visible to the eye, even if it be an emotion: do you recall the unnatural splash of white in a street scene in Caligari?) It will occur to you that the cut-back, the alternating exposition of two concurrent actions, the vision, the dream, are all good; and that the Close-up, dearest of all your findsl usually dissociates a face or an object from its moving background will alneda ris from what was done with you it in the early days.

I warn you again they were not great

Pictures except for The Avenging Conscience and-one you didn't make-Cabiria. To each of these a poet contributed. (Peace, Mr Griffith; the poet in your case was E. A. Poe; and the warrior poet of Fiume contributed the scenario for the second.) Mr Griffith contrived in his picture to project both beauty and terror by combining Annabel Lee with The Tell tale Heart. A sure instinct led him to disengage the vast emotion of longing and of lost love through an action of mystery and terror. (I think he made a happy ending somehow-by having the central portion of his story appear as a dream. How little it mattered since the real emotion came through the story.) The picture was projected in a palpable atmosphere; it was felt. After ten years I recall dark

[325]

masses and ghostly rays of light. And if I may anticipate the end, let me compare it with a picture of 1922, a picturization as you call it, of Annabel Lee. It was all scenery and captions; it presented a detestable little boy and a pretty little girl doing Tsthetic dancing along cliffs by the sea; one almost saw the Ocean View Hotel in the background. Mercilessly the stanzas appeared on the screen; but nothing was allowed to happen except a vulgar representation of calf love. I cannot bear to describe the disagreeable picture of grief at the end; I do not dare to think what you may now be preparing with a really great poem. The lesson is not merely one of taste; it is a question of knowing the camera, of realizing that you must project emotion by movement and by picture combined.

I am trying to trace for you the development of the serious moving picture as a bogus art, and I can't do better than assure you that it was best before it was an " art" at all. (Or I can indicate that slapstick comedy, which you despise, is not bogus, is a real, and valuable, ard delightful entertainment.) I believe that you went out West because the perpetual sun of southern California made taking easy; there you discovered the lost romance of America, its Wild West and its pioneer days, its gold rush and its Indians. You had it in your hands, then, to make that past of ours alive; a small written literature and a remnant of oral tradition remained for you to work

[326]

on. On the whole you did make a good beginning. You missed fine things, but you caught the simple ones; you presented the material directly, with appropriate sentiment. You relied on melodrama, which was the rightest thing you ever did. Comba and pursuit, the last-minute rescue, were the three items of your best pictilres; and your cutting department, carefully alternating the fight between white men and red with the slow-starting, distant, approaching, arriving, victorious troops from the garrison appealed properly to our soundest instincts. You went into the bad-man period; you began to make an individual soldier, Indian, bandit, pioneer, renegade, the focus of your interest: still good because you related him to an active, living background. Dear Heaven! before you had filmed Bret Harte you had created legendary heroes of your own.

Meanwhile Mr Griffith, apparently insatiable, was developing small genre scenes of slum life while he thought of filming the tragic history of the South after the war. Other directors sought other fields notably that of the serial adventure film. Since they made money for all concerned, you will not be surprised to hear these serials praised: The Exploits of Ela, one, the whole Pearl White adventure, the thirty minutes of action closing on an impossible and unresolved climax were, of course, infinitely better pictures than your version of Mr Joseph Conrad's Victory, your Humoreske, your Should a Wife For-

[327]

give? ' They were extremely silly; they worked too closely on a scheme: getting out of last week's predicament and into next week's can hardly be called a " form." But within their limitations they used the camera for all it was worth. It didn't matter a bit - flights and that the perils were preposterous, that the pursuits were all fakes composed by the speed of the projector. You were back in the days of Nick Carter and the Liberty Boys; you hadn't heard of psychology, and drama, and art; you were developing the camera. You bored us when your effects didn't come off and I'm afraid amused us a little even when they did. But you were on the right road.

There was very little acting in these films and in the Wild West exhibitions. There was a great deal of action. I can't recall Pearl White registering a single time; I recall only movement, which was excellent. It was later that your acting developed; up to this time you were working with people who hadn't succeeded in or were wholly ignorant of the technique of the stage; they moved before the camera gropingly at first, but gradually developing a technique suited to the camera and to nothing else. I am referring to days so far back that the old Biograph films used to be branded with the mark AB in a circle, and this mark occurred in the photographed sets to prevent stealing. In those days your actors and ac-

[328]

tresses were exceptionally naive and creative. You were on the point of discovering mass and line in the handling of crowds, in the defile of a troop, in the movement of individuals. Mr Griffith had already discovered that four men running in opposite directions along the design of a figure 8 gave the effect of sixteen men-a discovery lightly comparable to that of Velasquez in the crossed spears of the Surrender of Breda. You would have done well to continue your experiments with nameless individuals and chaotic masses; but you couldn't. You developed what you called person ali ties-and after that, actresses.

Before The Birth of a Nation was begun Mary Pickford had already left Griffith. I have heard that he vowed to make Mae Marsh a greater actress - as if she weren't one from the start, as if acting mattered, as if Mary Pickford ever could or needed to act. Remember that in The Avenging Conscience at least four people: Spottiswood Aiken, Henry Walthall, Blanche Sweet, and another I cannot identify the second villain-played superbly without acting.

Conceive your own stupidity in not knowing what Vachel Lindsay discovered: that " our Mary" was literally " the Queen of my People, " a radiant, lovely, childlike girl, a beautiful figurehead, a symbol of all our sentimentality. Why did you allow her to be come an actress? Why is everything associated with her later work so alien to beauty? You did not see her legend forming; you began to advertise her sal-

[329]

ary; you have, I believe unconsciously, tried to restore her now by giving her the palest role in all literature.) that of Marguerite in Faust. You are ten years too late. In the same ten years Blanche Sweet has almost disappeared and Mae Marsh has not arrived; Gishes and Talmadges and Swansons and other fatalities have triumphed. You have taken over the stage and the opera; you have filmed Caruso and Al Jolson, too, for all I know. You now have acting and no playing.

This is a matter of capital importance and I am willing to come closer to a definition. Acting is the way of impersonating, of rendering character, of presenting action which is suitable to the stage; it has, in the first place, a specific relation to the size of the stage and to that of the auditorium; it has also a second important relation to the lines spoken. Good actors-they are few-will always suit the gesture to the utterance in the sense that their gesture will be on the beat of the words; failure to know this ruined several of John Barrymore's soliloquies in Hamlet. Neither of these two primary and determinant circumstances affect the moving picture. It should be obvious that if good acting is adapted to the stage, nothing less than a miracle could make it also suitable to the cinema. The same thing is true of opera, which is in a desperate state because it f ailed to develop a type of representation adapted to musical instead of spoken expression. Opera and the pictures

[330]

both needed " playing" -by which I cover other forms of representation, of impersonation, characterization, without identifying them. It is unlikely that opera and pictures require the same kind of playing; but neither of them can bear acting. Chaplin, by the way, is a player, not an actor-although we all think of him as an actor because the distinction is tardily made. I should say that Mae Marsh, too, was a player in The Birth. So was H. B. Warner in a war play called Shell 49 (I am not sure of the figure); and there have been others. I have never seen Conrad Veidt or Werner Kraus on the stage; in Caligari they were players, not actors. Possibly since Kraus is considered the greatest of German actors, he acted so well that he seemed to be playing. But that requires genius and the Gishes have no genius.

The emergence of Mary Pickford and the production of The Birth of a Nation make the years 1911-14 the critical time of the movies. Nearly all your absurdities began about this time, including your protest against the word movies as no longer suited to the dignity of your art. From the success of The Birth sprang the spectacle film which was in trinsically all right and only corrupted Griffith and the pictures because it was unintelligently handled thereafter. From the success of Mary Pickford came the whole tradition of the movie as a genteel intellectual entertainment. The better side is the spectacle and the fact that in 1922 the whole mastery of

[331]

there ap ' peared from within the doorway the arm of their mother and with a gesture of unutterable loveliness it enlaced the boy's shoulders and drew him tenderly into the house. To have omitted the tears, to have shown nothing but the arm in that single curve of beauty, required, in those days, high imagination. It was i I li f the film; one felt from that moment at e rap the little girl was already understood in the vast suffering sympathy of the mother. So much Mr Griffith never again accomplished; it was the one moment when he stood beside Chaplin as a creative artistand it was ten years ago.

Of course if Griffith hasn't come through there is hardly anything to hope for from the others. Mr Ince always beat him in advertized expenditure; Fox was always cheaper and easier and had Annette Kellerman and did The Village Blacksmith. The logical outcome of Griffithism is in the pictures he didn't make: in When Knighthood Was in Flower and in Robin Hood, neither of which I could sit through. The lavishness of these films is appalling; the camera runs mad in everything but action, which dies a hundred deaths in as many minutes. Of what use are sets by Urban if the action which occurs in them is invisible to the naked eye. The old trick of using a crowd as a background and holding the interest in the individual has been lost; the trick of using the crowd as an individual hasn't been found

[334]

because we must have our love story. The spectacl film is slowly settling down to the level of the stereopticon slide.

Comparison with German films is inevitable. They are as much on the wrong track as we are; and the exception, Caligarl, is defective because in a proper attempt to believe the camera from the burden of recording actuality, the producers gave it the job of recording modern paintings for background. The acting was, however, playing; and the destruction of realism, even if it was accomplished by a questionable expedient, will have much to do with the future of the film. Yet even in the spectacle film the Germans managed to do something. Passion and Deception and the Pharaoh film and the film made out of Sumurun were not lavish. And in the manipulation of material (not of the instrument, where we know much more thap they) there came occasionally flashes of the real thing. In Deception there was a scene where the courtyard had to be cleared of an angry mob. Every American producer has handled the parallel scene and every one in the same way, centring in the middle between civilians and police.

What Lubitsch did was to form a single line of pike staffs and to show a solid mass of crowd-the feeling of hostility was projected in the opposition of line and mass. And slowly the space behind the pike staffs opened. The bright calm sunlight fell on a wider and widening strip of the courtyard. One was

[335]

hardly aware of struggle; all one saw was that gradually broadening patch of open, uncontested space in the light. And suddenly one knew that the courtyard was cleared, one seemed to hear the faint murmur of the crowd outside, and then silence. I am lost in admiration of this simplicity which involves every correct principle of the zsthetics of the moving picture. The whole thing was done with movement and light-the movement massed and the light on the open space. That is the true, the imaginative camera technique, which we failed to develop.'

The object of that technique is the indirect communication of emotion-indirect because that is the surest way, in all the arts, of multiplying the degree of intensity. The American spectacle film still communicates a thrill in the direct way of a highwayman with a blackjack. But the American serious film drama communicates not even this: it is at this moment entirely dead, or in other words, wholly bogus. I may be wrong in thinking that our present position develops out of the creation of Mary Pickford as a star. The result is the same.

For as soon as the movie became " the silent drama" it took upon itself responsibilities. It had to be dignified and artistic; it had to have literature

" I haven't seen The Covered Wagon. Its theme returns to the legendary history of America. There is no reason why it should not have been highly imaginative. But I wonder whether the thousands of prairie schooners one hears about are the film or the image. In the latter case there is no objection.

[336]

and actors and ideals. The simple movie plots no longer sufficed, and stage and novel were called upon to contribute their small share to the success of an art which seriously believed itself to be the consummation of all the arts. The obligation remained to choose only those examples which were suitable to the screen. It was, however, not adaptability which guided the choice, but the great name. Eventually everything was filmed because what couldn't be adapted could be spoiled. The degree of vandalism passes words; and what completed the ruin was that good novels were spoiled not to make good films, but to make bad ones. Victory was a vile film in addition to being a vulgar betrayal of Conrad; even the good Molnar with his exciting second-rate play, The Devil, found, himself so foully, so disgustingly changed on the screen that the whole idea, not a

great one, was lost and nothing remained but a sentimental vulgarity which had no meaning of its own, quite apart from any meaning of his. In each of these the elements are the same: a psychological development through an action. By corrupting the action the producers changed the idea; bad enough in itself, they failed to understand what they were doing and supplied nothing to take the place of what they had destroyed. The actual movies so produced refused to project any consecutive significant action whatsoever.

It would be futile to multiply examples-as fu-

[337]

tile as to note that there have been well-filmed novels and plays. The essential thing is that nearly every picture made recently has borrowed something, usually in the interest of dignity, gentility, refinement-and the picture side, the part depending upon action before the camera, has gone steadily down. Long subtitles explain everything except the lack of action. Carefully built scenes are settings in which nothing takes place. The climax arrives in the masterpieces of the de Mille school. They are " art." They are genteel. They offend nothing-except the intelligence. High life in the de Mille manner is not recognizable as decent human society, but it is refined, and the picture with it is refined out of existence. Ten years earlier there was another type of drama: the vamp, in short, and Theda Bara was its divinity. I have little to say in its defense because it was unalterably stupid (I don't say I didn't like it). But it wasn't half so pretentious as the de Mille social drama, and not half so vulgar. What it had to say, false or banal or ridiculous, it said entirely with the camera. It appealed to low passions and it truckled to imitative morality; there was in it a sort of corruption. Yet one could resist that frank ugliness as one can't resist the polite falsehood of the new culture of the movies.

It would be easy to exaggerate your failures. Your greatest mistake was a natural one-in taking over the realistic theatre. You knew that a photo-

[338]

graph can reproduce actuality without significantly transposing it, and you assumed that that was the duty of the film. But you forgot that the rhythm of the film was creating something, and that this creation adapted itself entirely to the projection of emotion by means not realistic, - that in the end the camera was as legitimately an instrument of distortion as of reproduction. You gave us, in short, the pleasure of verification in every detail; the Germans who are largely in the same tradition-they should have known better because their theatre knew better-improved the method at times and counted on significant detail. But neither of you gave us the pleasure of recognition. Neither you nor they have taken the first step (except in Caligari) toward giving us the highest degree of pleasure, that of escaping actuality and entering into a created world, built on its own inherent logic, keeping time in its own rhythm where we feel ourselves at once strangers and at home. That has been done elsewhere-not in the serious film.

I would be glad to temper all of this with praise: for Anita Loos' captions and John Emerson's occasionally excellent direction; for George Loane Tucker, for Monte Katterjohn's flashes of insight into what makes a scenario. I have liked many more films than I have mentioned here. But you are familiar with praise and there remains to say what you have missed. The moving picture when it became

[339]

pretentious, when it went upstage and said, " dear God, make me artistic" at the end of its prayers, killed its imagination and foreswore its popularity. At your present rate of progress you will in ten years-if you survive-be no more a popular art than grand opera is. You had in your hands an incalculable instrument to set free the imagination of mankind-and the atrophy of our imaginative lives has only been hastened by you. You had also an instrument of fantasy-and you gave us Marguerite Clark in films no better than the " whimsy-me" school of stage plays. Above all, you had something fresh and clean and new; it was a toy and should have remained a toy-something for our delight. You gave us problem plays. Beauty you neither understood nor cared for; and although you talked much about art you never for a moment tried to fathom the secret sources, nor to understand the secret obligations, of art.

Can you do anything now? I don't know and I am indifferent to your future-because there is a future for the moving picture with which you will have nothing to do. I do not know if the movie of the future will be popular-and to me it is the essence of the movie that it should be popular. Perhaps there will be a period of semi-popularity-it will be at this time that you will desert-and then the new picture will arrive without your assistance. For when you and your capitalizations and your publicity

[340]

go down together, the field will be left free for others. The first cheap film will startle you; but the film will grow less and less expensive. Presently it will be within the reach of artists. With players instead of actors and actresses, with fresh ideas (among which the idea of making a lot of money may be absent) these artists will give back to the screen the thing you have debauched-imagination. They will create with the camera, and not record, and will follow its pulsations instead of attempting to capture the rhythm of actuality. It isn't impossible to recreate exactly the atmosphere of Anderson's I'm a Fool; it isn't impossible (although it may not be desirable) to do studies in psychology; it is possible and desirable to create great epics of American industry and let the machine operate as a character in the play-just as the land of the West itself, as the corn must play its part. The grandiose conceptions of Frank Norris are not beyond the reach of the camera. There are painters willing to work in the medium of the camera and architects and photographers. And novelists, too, I fancy, would find much of interest in the scenario as a new way of expression.' There is no end to what we can accomplish.

The vulgar prettiness, the absurdities, the ignorances of your films haven't saved you. And although the first steps after you take away your guiding hand may be feeble, although bogus artists and

They have done so. See " The Cinema Novel."

[341]

Culture-hounds may capture the movie for a time in the end all will be well. For the movie is the imagination of mankind in action-and you haven't destroyed it yet.

Before a Picture by Picasso

(pages 344-392)

[344]

For there are many arts, not among those we conventionally call " fine, " which seem to me fundamental for living.

HAVELOCK ELLIS.

IT was my great fortune just as I was finishing this book to be taken by a friend to the studio of Pablo Picasso. We had been talking on our way of the lively arts; my companion denied none of their qualities, and agreed violently with my feeling about the bogus, what we called le grand Puccini. But he held that nothing is more necessary at the moment than the exercise of discrimination, that we must be on our guard lest we forget the major arts, forget even how to appreciate them, if we devote ourselves passionately, as I do, to the lively ones. Had he planned it deliberately he could not have driven his point home 'More deeply, for in Picasso's studio we found ourselves, with no more warning than our great admiration, in the presence of a masterpiece. We were not prepared to have an unframed canvas suddenly turned from the wall and to recognize immediately that one more had been added to the small number of the world's greatest works of art.

I shall make no effort to describe that painting. It isn't even important to know that I am right in my judgement. The significant and overwhelming thing to me was that I held the work a masterpiece and knew it to be contemporary. It is a pleasure to come upon an accredited masterpiece which preserve

[345]

its authority, to mount the stairs and see the Winged Victory and know that it is good. But to have the same conviction about something finished a month ago, contemporaneous in every aspect, yet associated with the great tradition of painting, with the indescribable thing we think of as the high seriousness of art and with a relevance not only to our life, but to life itself-that is a different thing entirely. For of course the first effect-after one had gone away and begun to be aware of effects-was to make one wonder whether it is worth thinking or writing or feeling about anything else. Whether, since the great arts are so capable of bei

|

|