Главная страница Случайная страница

Разделы сайта

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Physical Examination

|

|

After listening to the patient's complaints and becoming acquainted with the history of the present disease, social and housing conditions, and the family history, the physician should proceed to do a physical examination of the patient.

Objective study of the patient (status praesens) gives information on the condition of the entire body and the state of the internal organs. The general condition of the patient can be evaluated from the information given by the patient (psychic condition, asthenia, wasting, elevated temperature). The condition of separate organs can also be evaluated from the patient's complaints. More accurate information on the patient's general condition and separate organs can be obtained by special diagnostic procedures. It is necessary to remember that dysfunction of an organ always produces disorders in the whole body. In order to obtain full and systematic information on the patient's condition, physical examination should be carried out according to a predetermined plan. The patient is first given a general inspection, next the physician should use palpation, auscultation, percussion, and other diagnostic procedures by which the condition of the respiratory organs, the cardiovascular, gastro-intestinal and the urinary system, locomotion, lymph nodes, endocrine glands, and the nervous system may be examined. Laboratory tests, X-raying, and en-doscopy are objective methods of clinical examination.

Diagnostic methods can be divided into main and auxiliary. The main clinical methods include systematic inquiry, inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation, and measuring. Each patient should be examined repeatedly. These methods are called main because only after having applied them, the physician can decide what auxiliary methods (laboratory and instrumental tests) should be used to establish or verify the diagnosis.

Auxiliary investigation is often carried out by other specialists, rather than the physician. Auxiliary methods are no less important than the main ones and in some cases their results are decisive in establishing a correct diagnosis or locating the pathological focus (e.g. biopsy, endoscopy, X-ray examination, etc.).

Practical value of the main diagnostic methods can be assessed tentatively by statistics. According to some authors, anamnesis alone can be used for a correct diagnosis in 70 per cent cases with gastroduodenal pathology and ischaemic heart disease. According to other data, a physician can arrive at a correct diagnosis in 55 per cent cases from an anamnesis and inspection of the patient. A successful start of diagnostic examination encourages the physician and in more than 50 per cent cases it stimulates the diagnostic search in correct direction to help the physician correctly evaluate the personality of the patient (for whom this procedure becomes a kind of catharsis). Anamnesis restores retrospectively the course of the disease (errors however are likely to occur), whereas objective examination (status praesens) reflects the

present condition of the patient. Despite the great value of anamnesis, it is never sufficient for establishing a diagnosis: the conjectured diagnosis is confirmed by the main and auxiliary clinical examinations.

General Inspection

Despite the many instrumental and laboratory tests available at the present time, general inspection of the patient (inspectio) has remained an important diagnostic procedure for any medical specialist. The patient's condition on the whole can be assessed and a correct diagnosis can sometimes be made at " first sight" (acromegaly, toxic goitre, etc.). Pathological signs revealed during inspection of the patient are of great help in collecting an anamnesis and in further studies. In order to make the best possible inspection, the following special rules should be followed, which concern illumination during inspection, its technique and plan.

Illumination. The patient should be examined in the daytime, because electric light will mask any yellow colouring of the skin and the sclera. In addition to direct light, which outlines the entire body and its separate parts, side light will also be useful to reveal pulsation on the surface of the body (the apex beat), respiratory movements of the chest, peristalsis of the stomach and the intestine.

Inspection technique. The body should be inspected by successively uncovering the patient and examining him in direct and side light. The trunk and the chest are better examined when the patient is in a vertical posture. When the abdomen is examined, the patient may be either in the errect (upright) or supine (dorsal) position. The examination should be carried out according to a special plan, since the physician can miss important signs that otherwise could give a clue for the diagnosis (e.g. liver palm or spider angiomata which are characteristic of cirrhosis of the liver).

The entire body is first inspected in order to reveal general symptoms. Next, separate parts of the body should be examined: the head, face, neck, trunk, limbs, skin, bones, joints, mucosa, and the hair cover. The general condition of the patient is characterized by the following signs: consciousness and the psyche, posture and body-built.

Consciousness. It can be clear or deranged. Depending on the degree of disorder, the following psychic states are differentiated.

1. Stupor. The patient cannot orient himself to the surroundings, he

gives delayed answers. The state is characteristic of contusion and in some

cases poisoning.

2. Sopor. This is an unusually deep sleep from which the patient

recovers only for short periods of time when called loudly, or roused by an

external stimulus. The reflexes are preserved. The state can be observed in

some infectious diseases and at the initial stage of acute uraemia.

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

3. Coma. The comatose state is the full loss of consciousness with complete absence of response to external stimuli, with the absence of reflexes, and deranged vital functions. The causes of coma are quite varied but the loss of consciousness in a coma of any aetiology is connected with the cerebral cortex dysfunction caused by some factors, among which the most important are disordered cerebral circulation and anoxia. Oedema of the brain and its membranes, increased intracranial pressure, effect of toxic substances on the brain tissue, metabolic and hormone disorders, and also upset acid-base equilibrium are also very important for the onset of coma. Coma may occur suddenly or develop gradually, through various stages of consciousness disorders. The period that precedes the onset of a complete coma is called the precomatose state. The following forms of coma are most common.

Alcoholic coma. The face is cyanotic, the pupils are dilated, the respiration shallow, the pulse low and accelerated, the arterial pressure is low; the patient has alcohol on his breath.

Apoplexic coma (due to cerebral haemorrhage). The face is red, breathing is slow, deep, noisy, the pulse is full and rare.

Hypoglycaemic coma can develop during insulin therapy for diabetes.

Diabetic {hyperglycaemic) coma occurs in non-treated diabetes mellitus.

Hepatic coma develops in acute and subacute dystrophy and necrosis of the liver parenchyma, and at the final stage of liver cirrhosis.

Uraemic coma develops in acute toxic and terminal stages of various chronic diseases of the kidneys.

Epileptic coma. The face is cyanotic, there are clonic and tonic convulsions, the tongue is bitten. Uncontrolled urination and defaecation. The pulse is frequent, the eye-balls are moved aside, the pupils are dilated, breathing is hoarse.

4. Irritative disorders of consciousness may also develop. These are characterized by excitation of the central nervous system in the form of hallucinations, delirium (delirium furibundum due to alcoholism; in pneumonia, especially in alcoholics; quiet delirium in typhus, etc.).

General inspection can also give information on other psychic disorders that may occur in the patient (depression, apathy).

Posture of the patient. It can be active, passive, or forced.

The patient is active if the disease is relatively mild or at the initial stage of a grave disease. The patient readily changes his posture depending on circumstances. But it should be remembered that excessively sensitive or alert patients would often lie in bed without prescription of the physician.

Passive posture is observed with unconscious patients or, in rare cases, with extreme asthenia. The patient is motionless, his head and the limbs

hang down by gravity, the body slips down from the pillows to the foot end of the bed.

Forced posture is often assumed by the patient to relieve or remove pain, cough, dyspnoea. For example, the sitting position relieves ortho-pnoea: dyspnoea becomes less aggravating in cases with circulatory insufficiency. The relief that the patient feels is associated with the decreased volume of circulating blood in the sitting position (some blood remains in the lower limbs and the cerebral circulation is thus improved). Patients with dry pleurisy, lung abscess, or bronchiectasis prefer to lie on the affected side. Pain relief in dry pleurisy can be explained by the limited movement of the pleural layers when the patient lies on the affected side. If a patient with lung abscess or bronchiectasis lies on the healthy side, coughing intensifies because the intracavitary contents penetrate the bronchial tree. And quite the reverse, the patient cannot lie on the affected side if the ribs are fractured because pain intensifies if the affected side is pressed against the bed. The patient with cerebrospinal meningitis would usually lie on his side with his head thrown back and the thighs and legs flexed on the abdomen. Patients with angina pectoris and intermittent claudication prefer to stand upright. The patient is also erect (standing or sitting) during attacks of bronchial asthma. He would lean against the edge of the table or the chair back, with the upper part of the body slightly inclined forward. Auxiliary respiratory muscles are more active in this posture. The supine posture is characteristic of strong pain in the abdomen (acute appendicitis, perforated ulcer of the stomach or duodenum). The prone position (lying with the face down) is characteristic of patients with tumours of the pancreas and gastric ulcer (if the posterior wall of the stomach is affected). Pressure of the pancreas on the solar plexus is lessened in this posture.

Habitus. The concept of habitus includes the body-build, i.e. constitution, height, and body weight.

Constitution (L constituero to set up) is the combination of functional and morphological bodily features that are based on the inherited and acquired properties, and that account for the body response to endo- and ex-ogenic factors. The classification adopted in the Soviet Union (M. Cher-norutsky) differentiates between the following three main constitutional types: asthenic, hypersthenic, and normosthenic.

The asthenic constitution is characterized by a considerable predominance of the longitudinal over the transverse dimensions of the body by the dominance of the limbs over the trunk, of the chest over the abdomen. The heart and the parenchymatous organs are relatively small, the lungs are elongated, the intestine is short, the mesenterium long, and the diaphragm is low. Arterial pressure is lower than in hypersthenics; the vital capacity of the lungs is greater, the secretion and peristalsis of the

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

stomach, and also the absorptive power of the stomach and intestine are decreased; the haemoglobin and red blood cells counts, the level of cholesterol, calcium, uric acid, and sugar in the blood are also decreased. Adrenal and sexual functions are often decreased along with thyroid and pituitary hyperfunction.

The hypersthenic constitution is characterized by the relative predominance of the transverse over the longitudinal dimensions of the body (compared with the normosthenic constitution). The trunk is relatively long, the limbs are short, the abdomen is large, the diaphragm stands high. All internal organs except the lungs are larger than those in asthenics. The intestine is longer, the walls are thicker, and the capacity of the intestine is larger. The arterial pressure is higher; haemoglobin and red blood cell count and the content of cholesterol are also higher; hypermobility and hypersecretion of the stomach are more normal. The secretory and the absorptive function of the intestine are high. Thyroid hypofunction is common, while the function of the sex and adrenal glands is slightly increased.

Normosthenic constitution is characterized by a well proportioned make-up of the body and is intermediate between the asthenic and hypersthenic constitutions.

The posture or attitude of the patient is often indicative of his general tone, the degree of muscle development, and sometimes of his occupation and habits. Most patients with grave diseases or with psychic depression are often stooped. Erect posture, easy gait, and free and unconstrained movements indicate the normal condition of the body. Some gaits are specific for certain diseases of the nervous system (hemiplegia, sciatica, etc.). Surgical diseases of the bones and joints, rheumatism, or deranged blood circulation in the lower extremities change the gait and make walking difficult. The so-called waddling gait is characteristic of osteomalacia or congenital dislocation of the femur.

During the general inspection, the physician should pay attention to the open parts of the patient's body, the head, the face and the neck.

Changes in the size and shape of the head can give diagnostic clues. Excessive growth of the skull occurs in hydrocephalus. An abnormally small head is typical of microcephalus, which is also marked by mental under development. A square head, flattened on top, with prominent frontal tubers, can indicate congenital syphilis or rickets in past history. The position of the head is also important in diagnosing cervical myositis or spondylarthritis. Involuntary movements of the head (tremor) are characteristic of parkinsonism. Rhythmical movements of the head in synchronism with the cardiac pulse are characteristic of aortic incompetence (Musset's sign). The presence of scars on the head may suggest the cause of persistent headache. It is necessary to find out whether the patient has ver-

tigo which is typical particularly for Meniere's syndrome, or epileptiform attacks.

Countenance. The facial expression can indicate the mental composure and various psychic and somatic conditions. It also depends on age and sex and can therefore give diagnostic clues when diagnosing some endocrine disorders (woman-like expression in men and masculine features in women). The following changes in the face are diagnostically essential:

1. A puffy face is observed in (a) general oedema characteristic of renal

diseases; (b) local venous congestion in frequent fits of suffocation and

cough; (c) compression of lymph ducts in extensive effusion into the

pleural and pericardial cavity, in tumours of mediastinum, enlarged

mediastinal lymph nodes, adhesive mediastinopericarditis, compressed

superior vena cava (Stokes' collar).

2. Corvisart's facies is characteristic of cardiac insufficiency. The face

is oedematous, pale yellowish, with a cyanotic hue. The mouth is always

half open, the lips are cyanotic, the eyes are dull and the eyelids sticky.

3. Facies febrilis is characterized by hyperaemic skin, sparkling eyes

and excited expression. There are special features of facies febrilis

characteristic of some infectious diseases: feverish redness in acute lobar

pneumonia (more pronounced on the side of the affected lung); general

hyperaemia of the puffy face is characteristic of louse-borne typhus, the

sclera is injected (" rabbit eye" according to F. Yankovsky); slightly icteric

yellow colour is characteristic of typhoid fever. Tuberculosis patients with

fever have " burning" eyes on an exhausted and pale face with blush

localized on the cheeks. An immobile face is characteristic of septic fever;

the face is pale, sometimes slightly yellowish.

4. Face and its expression are altered in various endocrine disorders; (a)

a face (Fig. 3) with enlarged promient parts (such as nose, chin, and cheek

bones) and enlarged hands are characteristic of acromegalia (hands become

enlarged in some pregnancies); (b) myxoedematous face indicates thyroid

hypofunction; the face may be uniformly puffy with oedematous mucosa,

narrowed eye slits, the face features smoothed down, the hair is absent on

the outward portions of the eyebrow; the presence of a blush on a pale face

resembles the appearance of a doll; (c) facies basedovica (see Fig. 112): this

is the face of a patient with thyroid hyperf unction; the face is lively with

widened eye slits and abnormally sparkling eyes; the eyes are protruded

and the face looks as if frightened; (d) an intense red, moon-like glittering

face with a beard and mustaches in women is characteristic of the Itsenko-

Cushing disease.

5. Facies leontina with nodular thickening of the skin under the eyes

and over the brows, with flattened nose is observed in leprosy.

6. Parkinson's mask (or facies) is an amimic face characteristic of

encephalitis patients.

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

Fig. 3. The face of a patient with acromegaly.

7. A slightly puffy wax-doll, very pale face with a yellowish tint, and

seemingly tranlucent skin, is characteristic of Addison-Biermer anaemia.

8. Risus sardonicus with a semblance of a grin occurs in tetanus pa

tients: the mouth widens as in laughter, while the skin folds on the

forehead express grief.

9. Facies hippocratica (first described by Hippocrates) is associated

with collapse in grave diseases of the abdominal organs (diffuse peritonitis,

perforated ulcer of the stomach or duodenum, rupture of the gall bladder).

The face is characterized by sunken eyes, pinched nose, deadly livid and

cyanotic skin, which is sometimes covered with large drops of cold sweat.

10. Asymmetric movements of facial muscles indicate a history of

cerebral haemorrhage or facial neuritis.

Inspection of the eyes and eyelids can reveal some essential diagnostic signs. Oedema of the eyelids, especially of the lower eyelids, is the first indication of acute nephritis; it is also observed in anaemia, frequent attacks of cough, and deranged sleep; oedema of the eyelids can also occur in the morning in healthy persons as well.

The colour of the eyelids is important. The eyelids are dark in diffuse toxic goitre and Addison disease. Xanthomas indicate deranged cholesterol metabolism. A dilated eye slit with the eyelids that do not close is characteristic of paralysis of the facial nerve; persistent drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis) is an important sign of some affections of the nervous system. Narrowing of the eye slit occurs in myxoedema and general oedema of the face. Exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball) is observed

in thyrotoxicosis, retrobulbar tumours, and also in strong myopia. Recession of the eyeball in the orbit (enophthalmos) is typical of myxoedema and is an important sign of " peritoneal face". Unilateral recession of the eye into the orbit attended by narrowing of the eye slit, drooping of the upper eyelid and narrowing of the pupil, is the Homer's (Bernard-Horner) sydrome caused by the affection of the pupil sympathetic innervation of the same side (due to various causes).

The shape of the pupils, their symmetry, response to light, accommodation and convergence, and also their " pulsation" are of great diagnostic significance in certain diseases. Abnormally contracted pupil (miosis) is observed in uraemia, tumours and intracranial haemorrhages, and in morphine poisoning. Enlargement of the pupil (mydriasis) occurs in comatose states (except uraemic coma) and cerebral haemorrhages, and also in atropine poisoning. Anisocoria (unequal size of the pupils) occurs in some affections of the nervous system. Squinting results from paralysis of the ocular muscles due to lead poisoning, botulism, diphtheria, affections of the brain and its membranes (syphilis, tuberculosis, meningitis, cerebral haemorrhage).

The size of the nose may attract attention providing some diagnostic signs, e.g. it has an abnormal size in acromegaly, or its shape deviates from the normal in rhinoscleroma. The nose may be sunken as a result of syphilis in the past history (saddle nose). Soft tissues of the nose are disfigured in lupus.

When inspecting the mouth attention should be paid to its shape (symmetry of the angles, permanently open mouth), the colour of the lips, eruption on the lips (cold sores, herpes labialis), and the presence of fissures. The oral mucosa should also be inspected (for the presence of aphthae, pigmentation, Filatov-Koplik spots, thrush, contagious aphthae of the foot and mouth disease, haemorrhage). Marked changes in the gums can be observed in some diseases (such as pyorrhoea, acute leukaemia, diabetes mellitus, and scurvy) and poisoning (with lead or mercury). The teeth should be examined for the absence of defective shape, size, or position. The absence of many teeth is very important in the aetiology of some alimentary diseases. Caries is the source of infection and can affect some other organs.

Disordered movement of the tongue may indicate nervous affections, grave infections and poisoning. Marked enlargement of the tongue is characteristic of myxoedema and acromegaly; less frequently it occurs in glossitis. Some diseases are characterized by the following abnormalities of the tongue: (1) the tongue is clear, red, and moist in ulcer; (2) crimson-red ln scarlet fever; (3) dry, with a brown coat and grooves in grave poisoning and infections; (4) coated in the centre and at the root, but clear at the tip

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

and margins in typhoid fever; (5) smooth tongue without papillae (as if polished) is characteristic of Addison-Biermer disease. The glassy tongue is characteristic of gastric cancer, pellagra, sprue, and ariboflavinosis; (6) local thickening of the epithelium is characteristic of smokers (leucoplakia). Local pathological processes, such as ulcers of various aetiology, scars, traces left from tongue biting during epileptic fits, etc., are also suggestive of certain diseases.

During inspection of the neck attention should be paid to pulsation of the carotid artery (aortic incompetence, thyrotoxicosis), swelling and pulsation of the external jugular veins (tricuspid valve insufficiency), enlarged lymph nodes (tuberculosis, lympholeukaemia, lym-phogranulomatosis, cancer metastases), diffuse or local enlargement of the thyroid gland (thyrotoxicosis, simple goitre, malignant tumour).

The colour, elasticity, and moisture of the skin, eruptions and scars are important. The colour of the skin depends on the blood filling of cutaneous vessels, the amount and quality of pigment, and on the thickness and translucency of the skin. Pallid skin is connected with insufficiency of blood circulation in the skin vessels due to their spasms of various aetiology or acute bleeding, accumulation of blood in dilated vessels of the abdominal cavity in collapse, and in anaemia. In certain forms of anaemia, the skin is specifically pallid: with a characteristic yellowish tint in Addison-Biermer anaemia, with a greenish tint in chlorosis, earth-like in malignant anaemia, brown or ash-coloured in malaria, cafe au lait in subacute septic endocarditis. Pallid skin can also be due to its low translucency and considerable thickness; this is only apparent anaemia, and can be observed in healthy subjects.

Red colour of the skin can be transient in fever or excess exposure to heat; persistent redness of the skin can occur in subjects who are permanently exposed to high temperatures, and also in erythraemia. Cyanotic skin can be due to hypoxia in circulatory insufficiency (Plate 1), in chronic pulmonary diseases, etc. Yellowish colour of the skin and mucosa can be due to upset secretion of bilirubin by the liver or due to increased haemolysis. Dark red or brown skin is characteristic of adrenal insufficiency. Hyperpigmentation of the breast nipples and the areola in women, pigmented patches on the face and the white line on the abdomen are signs of pregnancy. When silver preparations are taken for a long time, the skiri becomes grey on the open parts of the body (argyria). Foci of depigmenta-tion of the skin (vitiligo) also occur.

The skin can be wrinkled due to the loss of elasticity in old age, in prolonged debilitating diseases and in excessive loss of water.

Elasticity and turgor of the skin can be determined by pressing a fold of skin (usually on the abdomen or the extensor surface of the arm) between

the thumb and the forefinger. The fold disappears quickly on normal skin when the pressure is released while in cases with decreased turgor, the fold persists for a long period of time.

Moist skin and excess perspiration are observed in drop of temperature in patients recovering from fever and also in some diseases such as tuberculosis, diffuse toxic goitre, malaria, suppuration, etc. Dry skin can be due to a great loss of water, e.g. in diarrhoea or persistent vomiting (toxicosis of pregnancy, organic pylorostenosis).

Eruptions on the skin vary in shape, size, colour, persistence, and spread. The diagnostic value of eruptions is great in some infections such as measles, German measles, chicken- and smallpox, typhus, etc. Roseola is a rash-like eruption of 2—3 mm patches which disappears when pressed. This is due to local dilatation of the vessels. Roseola is a characteristic symptom of typhoid fever, para-typhus, louse-borne typhus, and syphilis.

Erythema (Plate 2) is a slightly elevated hyperaemic portion of the skin with distinctly outlined margins. Erythema develops in some persons hypersensitive to strawberries, eggs, and canned crabs. Erythema can develop after taking quinine, nicotinic acid, after exposure to a quartz lamp, and also in some infectious diseases, such as erysipelas and septic diseases.

Weals (urticaria, nettle rash) appear on the skin as round or oval itching lesions resembling those which appear on the skin bitten by stinging nettle. These eruptions develop as an allergic reaction.

Herpetic lesions are small vesicles 0.5 to 1 cm in size. They are filled with transparent fluid which later becomes cloudy. Drying crusts appear in several days at the point of the collapsed vesicles. Herpes would normally affect the lips (herpes labialis, or cold sore) and the ala nasi (herpes nasalis). Less frequently herpetic lesions appear on the chin, forehead, cheeks, and ears. Herpetic lesions occur in acute lobar pneumonia, malaria, and influenza.

Purpura is a haemorrhage into the skin (Plate 3) occurring in Werlhoff's disease, haemophilia, scurvy, capillarotoxicosis, and longstanding mechanical jaundice. The lesions vary in size from small pointed haemorrhages (petechiae) to large black and blue spots (ecchymoses).

Lesions of the skin are quite varied in character when they appear as allergic manifestations.

Desquamation of the skin is of great diagnostic value. It occurs in debilitating diseases and many skin diseases. Scars on the skin, e.g. on the abdomen and the hips, remain after pregnancy (striae gravidarum), in Itsenko-Cushing disease, and in extensive oedema. Indented stellar scars, tightly connected with underlying tissues, are characteristic of syphilitic af-tections. Postoperative scars indicate surgical operations in past history.

■ 4-1556

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

Cirrhosis of the liver is often manifested by development of specific vascular stellae (telangiectasia). This is a positive sign of this disease.

Abnormal growth of hair is usually due to endocrine diseases. Abnormally excessive growth of hair (hirsutism, hypertrichosis) can be congenital, but more frequently it occurs in adrenal tumours (Itsenko-Cushing sydrome) and tumours of the sex glands. Deficient hair growth is characteristic of myxoedema, liver cirrhosis, eunuchoidism, and infantilism. Hair is also affected in some skin diseases.

Nails become excessively brittle in myxoedema, anaemia and hypovitaminosis, and can also be found in some fungal diseases of the skin. Flattened and thickened nails are a symptom of acromegaly. Nails become rounded and look like watch glass in bronchiectasis, congenital heart diseases and some other affections.

Subcutaneous fat can be normal or to various degrees excessive or deficient. The fat can be distributed uniformly or deposited in only certain parts of the body. Its thickness is assessed by palpation. Excessive accumulation of subcutaneous fat (adiposis) can be due to either exogenic (overfeeding, hypodynamia, alcoholism, etc.) or endogenic factors (dysfunction of sex glands, the thyroid, or pituitary gland) (Plate 4). Insufficient accumulation of subcutaneous fat may result from constitutional factors (asthenic type), malnutrition, or alimentary dysfunction. Excessive wasting is referred to as cachexia, and may occur in prolonged intoxication, chronic infections (tuberculosis), malignant newgrowths, diseases of the pituitary, thyroid and pancreas, and in some psychological disorders as well. Weighing the patient gives additional information about his diet and is an objective means in following up on the patient's weight changes during the treatment of obesity or cachexia.

Oedema can be caused by penetration of fluid through the capillary walls and its accumulation in tissues. Accumulated fluid may be congestive (transudation) or inflammatory (exudation). Local oedema is a result of some local disorders in the blood or lymph circulation; it is usually associated with thrombosis of the veins, that is, compression of the veins by tumours or enlarged lymph nodes. General oedema associated with diseases of the heart, kidneys or other organs is characterized by general distribution of oedema throughout the entire body (anasarca) or by symmetrical localization in limited regions of the body. These phenomena can be due to the patient lying on one side. If oedema is generalized and considerable, transudate may accumulate in the body's cavities: in the abdomen (ascites), pleural cavity (hydrothorax) and in the pericardium (hydropericardium). Examination reveals swollen glossy skin. The specific relief features of the oedema-affected parts of the body disappear due to the levelling of all irregularities on the body surface. Stretched and tense skin appears transparent in oedema, and is especially apparent on loose

subcutaneous tissues (the eyelids, the scrotum, etc.). In addition to observation, oedema can also be revealed by palpation. When pressed by the finger, the oedematous skin overlying bones (external surface of the leg, malleolus, loin, etc.) remains depressed for 1-2 minutes after the pressure is released. The mechanism of the development of oedema and methods to reveal this condition will be discussed in detail in the special section of this textbook.

Normal lymph nodes cannot be detected visually or by palpation. Depending on the character of the process, their size varies from that of a pea to that of an apple. In addition to simple inspection, the physician should resort to palpation in order to make a conclusion on the condition of the lymphatic system. Attention should be paid to the size of the lymph nodes, their tenderness, mobility, consistency and adherence to the skin. Submandibular, axillary, cervical, supraclavicular, and inguinal lymph nodes are commonly enlarged. Submandibular nodes swell in the presence of inflammation in the mouth. Chronic enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes is associated with development of tuberculosis in them, which is characterized by purulent foci with subsequent formation of fistulae and immobile cicatrices.

Cancer of the stomach and, less frequently, cancer of the intestine can metastasize into the lymph nodes of the neck (on the left). The axillary lymph nodes are sometimes enlarged in mammary cancer. In the presence of metastases the lymph nodes are firm, their surface is rough, palpation is painless. Tenderness of a lymph node in palpation and reddening of the overlying skin indicates inflammation in the node. Systemic enlargement of the lymph nodes is observed in lympholeukaemia, lymphogranulomatosis, and lymphosarcomatosis. In lymphatic leukaemia and lymphogranuloma the nodes fuse together but do not suppurate. Puncture or biopsy of the lymph nodes is required to diagnose complicated cases.

During examination of the muscular system the physician should assess its development, which depends on the patient's occupation, his sporting habits, etc. Local atrophy of muscles, especially muscles of the extremities, is diagnostically important. Atrophy can be determined by measuring the girth of the symmetrical muscles of both extremities. Determination of muscular strength and detection of functional muscular disturbances (cramps) are also important for diagnosis. Muscular dysfunction may occur in renal insufficiency (eclampsia), disorders of the liver (hepatic insufficiency), affections of the central nervous system (meningitis), tetanus, cholera, etc.

Defects (deformities or bulging) of the bones of the skull, chest, spine, and the extremities, may be revealed by external inspection. But in many ^ palpation is necessary. Peripheral bones of the extremities (of the

ers, toes), cheek bones or the mandible grow abnormally in acromega-

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

ly. Rachitic changes occur in the form of the so-called pigeon breast, rachitic rosary (beading at the junction of the ribs with the cartilages), deformities of the lower extremities, etc. Tuberculotic lesions (the so-called haematogenic osteomyelitis) are localized mainly in the epiphyses of the bones, with formation of fistulae through which pus is regularly discharged. Multiple affections of the flat bones of the skeleton (the skull included) that can be seen radiographically as round light spots (bone tissue defects) are typical of myeloma. Diseases of the spine cause deformation of the spinal column and the chest. Considerable deformities of the spine (kyphosis, scoliosis) can cause dysfunction of the thoracic organs.

When examining the joints, attention should be paid to their shapes, articulation, tenderness in active or passive movements, oedema, and hyperaemia of the adjacent tissues. Multiple affections of large joints are characteristic of exacerbated rheumatism. Rheumatoid arthritis affects primarily small joints of the hands with their subsequent deformation. Metabolic polyarthritides, e.g. in gout, are characterized by thickening of the terminal phalanges of the fingers and toes (so-called Heberden's nodes). Monarthritis (affection of one joint) would be usually observed in tuberculosis and gonorrhoea.

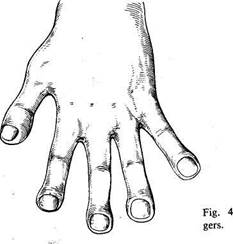

Examination of the extremities can reveal varicosity of the veins, oedema, changes in the skin, muscles, tremor of the extremities, deformities, swelling and hyperaemia of the joints, ulcers, and scars. Diseases of the central nervous system (tumous, cerebral haemorrhage) and also of the peripheral nervous system can cause atrophy and paralysis of the muscles. Hippocratic fingers (Fig. 4) or clubbing of the terminal phalanges of the fingers and toes are important diagnostically. The changed shape of the

|

Hippocratic fin-

nails resembles hour glass. This symptom is characteristic of prolonged diseases of the lung (chronic purulent processes), heart (subacute septic endocarditis, congenital heart defects) and liver (cirrhosis). Periodically occurring vascular spasms in the extremities cause the development of the symptom known as the dead finger, transient pallor of the fingers and toes, which is characteristic of Raynaud's disease. Prolonged spasms of blood vessels can cause gangrene of the fingers.

When examining the legs, attention should be paid to possible flat foot. Saber shins occur in rickets and sometimes in syphilis. Uneven thickening of the leg bones indicates periostitis which can sometimes be of syphilitic aetiology.

Palpation

Palpation (L palpare to touch gently) is the clinical method by which the physical properties, topographic correlation, tenderness and functional characteristic of tissues and organs can be studied by the sense of touch.

Palpation has been known since the ancient times. Hippocrates mentioned palpation in his works. But this method was formerly used mainly to study the physical properties of superficially located organs, e.g. the skin, joints, bones, or pathological growths (tumours), and also for feeling the pulse. It was only recently that physicians began using palpation to detect physiological phenomena. For example, physicians began studying vocal fremitus and the apex beat by palpation only in the middle of the last century (Laennec, Skoda), while systematic use of palpation of the abdominal cavity was begun late in the 19th century, mainly after publication of works by Botkin, Glenard, Obraztsov, and Strazhesko.

The history of development of palpation technique emphasizes the importance of experience and exercise and also of a thoroughly developed methodology for palpation of various parts of the body. The physiological base of palpation is the sense of touch of the examining fingers, and also feeling of temperature. When an organ or growth is palpated through a separating medium (e.g. through the abdominal wall), the examiner obtains useful information only if the density of the palpated organ is higher than that of the separating medium. A relatively soft object, e.g. the intestine, can be felt by pressing the intestine against the hard underlying tissues (pelvic bones, the palm of the examiner pressed against the loin).

Palpation is widely used as an important method for diagnosis of diseases of the internal organs, muscles and bones, lymphatic system, and tne skin. Depending on the object of examination, palpation technique dif-fers for examining various organs and systems, but the physician should ^ follow a certain plan in his manipulations. Neglect of this rule gives

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

obscure and sometimes erroneous results. For example, the skin or muscles are felt in a fold; this gives information on the thickness, elasticity, and other properties of the material felt. In order to feel temperature of separate parts of the body, the physician should place his palms flat on the body or the extremities, on symmetrical joints (the skin overlying the affected joint is warmer), etc. The pulse is determined by feeling the skin over the artery 'by the fingers; the properties of the arterial wall and the character of the pulse can thus be determined. Palpation is used to reveal vocal fremitus; this method is useful for the diagnosis of diseases of the lungs and the pleura. Palpation is also very important for the diagnosis of diseases of the abdominal organs. Special techniques used for this purpose will be described in detail in relevant sections. Special palpation techniques are used in obstetrics, gynaecology, and urology.

Deep and surface palpation are differentiated. (A variant of deep palpation is penetrating palpation during which the finger tip is impressed into the body to determine the painful area.) Among other palpation techniques are bimanual palpation (with both hands) and ballotment of firm organs (liver, spleen, tumours) in the abdomen containing much fluid, kneepan (exudate in the knee joint), etc. Obraztsov and Strazhesko developed a palpating technique known as sliding palpation, which is used for studying organs located deep in the abdomen.

Despite the wide use of radiography for the diagnosis of diseases of bones, and especially of joints, palpation still remains an important diagnostic technique and is the first and indispensable method for examining the lymph nodes. Palpation is especially important in the study of clinical anatomy and the physiology of the internal organs (along with other direct methods of diagnostic examination).

Percussion

Percussion (L percutere to strike through) was first proposed by an Austrian physician Auenbrugger in 1761. Tapping various parts of the human body produces sounds by which one can learn about the condition of the underlying organs. The organs or tissues lying beneath the percussed area begin vibrating and these vibrations are transmitted to the surrounding air whose vibration is perceived by our ears as sounds. Liquids and airless tissues give dull sounds which can be heard with difficulty, such as the sound of a percussed femur (femoral sound). Airless organs and also liquids cannot therefore be differentiated by percussion. The properties of each particular sound obtained by percussion of the chest or the abdomen, and differing from the femoral sound, depend on the amount of air or gas enclosed within the chest or abdomen. The difference in the sounds of percussed lungs, liver, spleen, heart, stomach and other organs depends on (a)

|

Fig. 5. Correct position of the hands during finger-to-finger percussion.

the different amount of gas or air inside or round the percussed organ; (b) tension of the tissue; and (c) different strength of the percussion stroke transmitted to this gas or air.

Percussion is done by tapping with a plexor (hammer) on a pleximeter placed on the body, or by a finger on another finger (Fig. 5). This is mediate percussion. In immediate percussion the examined part of the body is struck directly by the soft tip of the index finger. To make tapping stronger, the index finger may be first held by the side of the middle finger and then released. This method was proposed by Obraztsov. Its advantage is that the striking finger feels the resistance of the examined part of the body.

Percussion is done with a slightly flexed middle finger on the dorsal side of the second phalanx of the middle finger of the opposite hand, which is pressed tightly against the examined part of the body. Percussion should be done by the movement of the wrist alone without involving the forearm into the movement. Striking intensity should be uniform, blows must be quick and short, directed perpendicularly to the intervening finger. Tapping should not be strong.

Sounds obtained by percussion differ in strength (clearness), pitch, and tone. Sounds may be strong and clear (resonant) or soft and dull; they may be high or low, and either tympanic or non-tympanic (and with metallic tinkling).

Resonance (clearness) of the percussion sound largely depends on the vibration amplitude: the stronger the tapping the louder is the sound; uniform strength of tapping is therefore required. A louder sound will be heard during percussion of an organ containing greater amount of air. In healthy persons resonant and clear sounds are heard in percussion of

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

thoracic and abdominal organs filled with gas or air (lungs, stomach, intestine).

Soft or dull sound is heard during percussion of the chest and the abdominal wall overlying airless organs (liver, heart, spleen), and also during percussion of muscles (femoral sound). Resonant and clear sound will become soft if the amount of air decreases inside the lung or if liquid is accumulated between the lungs and the chest wall (in the pleural cavity).

The pitch of the sound depends on the vibration frequency: the smaller the volume of the examined organ, the higher the vibration frequency, hence the higher the pitch. Percussion of healthy lungs in children gives higher sounds than in adults. The sound of a lung containing excess air (emphysema) is lower than that of a healthy lung. This sound is called bandbox. Normal vibration frequency of a healthy lung during percussion is 109-130 per second, while in emphysema the frequency decreases to 70-80 c/s. Quite the opposite, if the pulmonary tissue becomes more consolidated, the frequency increases to 400 c/s and more.

The tympanic sound resembles the sound of a drum (hence its name: Gk tympanon drum). Tympany differs from a non-tympanic sound by higher regularity of vibrations and therefore it approaches a musical tone, while a non-tympanic sound includes many aperiodic vibrations and sounds like noise. A tympanic sound appears when the tension in the wall of an air-containing organ decreases. Tympany can be heard during percussion of the stomach and the intestine of healthy people. Tympany is absent during percussion of healthy lungs, but if the tension in the pulmonary tissue decreases, tympanic sounds can be heard. This occurs in incomplete compression of the lung by the pleural effusion, in inflammation or oedema of the lung (the percussion sound then becomes dull tympanic). A tympanic sound can also be heard if air cavities are formed in the lungs or when air penetrates the pleural cavity. Tympany is heard over large caverns and in open pneumothorax (the sound is resonant). Since air-filled organs produce resonant percussion sounds and airless organs give dull sounds, the difference between these sounds helps locate the borders between these organs (e.g. between the lungs and the liver, the lungs and the heart, etc.).

Topographic percussion is used to determine the borders, size and shape of organs. Comparison of sounds on symmetrical points of the chest is called comparative percussion.

Tapping strength can vary depending on the purpose of the examination. Loud percussion (with a normal force of tapping), light, and lightest (threshold) percussion are differentiated. The heavier the percussion stroke, the greater is the area and depth to which the tissues are set vibrating, and hence the more resonant is the sound. In heavy or deep percussion, tissues lying at a distance of 4- 7 cm from the pleximeter are involved. In light or surface percussion the examined zone has the radius of

2- 4 cm. Heavy percussion should therefore be used to examine deeply located organs, and light percussion for examining superficial organs. Light percussion is used to determine the size and borders of various organs (liver, lungs and heart). The lightest percussion is used to determine absolute cardiac dullness. The force of the percussion stroke should be the slightest (at the threshold of sound perception). The Goldscheider method is often used for this purpose, the middle finger (flexor) of the right hand is used to tap the middle finger of the left hand flexed at the second phalanx and placed at a right angle touching the surface only with the soft tip of the terminal phalanx (pleximeter).

Main rules of percussion. 1. The patient should be in a comfortable posture and relaxed. The best position is standing or sitting. Patients with grave diseases should be percussed in the lying position. When the patient is percussed from his back, he should be sitting on a chair, his face turned to the chair back. The head should be slightly bent forward, his arms should rest against his lap. In this position muscle relaxation is the greatest and percussion thus becomes more easy.

2. The room should be warm and protected from external noise.

3. The physician should be in a comfortable position as well.

4. A pleximeter or the middle finger of the left hand, which is normally

used in the finger-to-finger percussion, should be pressed tightly to the ex

amined surface. The neighbouring fingers should be somewhat set apart

and tightly pressed to the patient's body. This is necessary to delimit pro

pagation of vibrations arising during percussion. The physician's hands

should be warm.

5. The percussion sound should be produced by the tapping movement

of the hand alone. The sound should be short and distinct. Tapping should

be uniform, the force of percussion strokes depending on the object being

examined (see above).

6. In topographic percussion, the finger or the pleximeter should be

placed parallel to the anticipated border of the organ. Organs giving reso

nant note should be examined first: the ear will better detect changes in

sound intensity. The border is marked by the edge of the pleximeter

directed toward the zone of the more resonant sounds.

7. Comparative percussion should be carried out on exactly sym-

metrical parts of the body.

Auscultation

Auscultation (L auscultare to listen) means listening to sounds inside the body. Auscultation is immediate {direct) when the examiner presses his J? 1 to the patient's body, or mediate (indirect, or instrumental). Auscultation was first developed by the French physician Laennec in 1816. In 1819

General Part

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

it was described and introduced into medical practice. Laennec also invented the first stethoscope. He substantiated the clinical value of auscultation by checking its results during section. He described and named almost all the auscultative sounds (vesicular, bronchial respiration, crepitation, murmurs). Thanks to Laennec, auscultation soon became an important method for diagnostication of lung and heart disease and was acknowledged throughout the world, Russia included. The first papers devoted to auscultation methods were published in Russia in 1824.

The development of auscultation technique is connected with improvement of the stethoscope (Piorri, Yanovsky, and others), invention of the binaural stethoscope (Filatov and others), invention of the phonen-doscope, and the study of the physical principles of auscultation (Skoda, Ostroumov, Obraztsov, and others). Elaboration of methods for recording sounds (phonography) that arise in various organs has become a further development of auscultation. The graphic record of heart sounds was first made in 1894 by Einthoven. Improved phonographic technique made it possible to solve many important auscultation problems and showed the importance of this diagnostic method.

Respiratory act, cardiac contractions, movements in the stomach and the intestine produce vibrations in the surrounding tissues. Some of these vibrations reach the surface of the body and can thus be heard directly by the physician's ear or by using a phonendoscope. Both direct and indirect auscultation is used in practical medicine. Immediate or direct auscultation is more effective (heart sounds and slight bronchial respiration are better heard by direct auscultation) because the sounds are not distorted and are taken from over a larger surface (the area covered by the physician's ear is larger than that of the stethoscope chest piece, or bell). Immediate auscultation is impractical for auscultation of the supraclavicular fossa and armpits and sometimes for hygienic considerations. Mediate (instrumental) auscultation ensures better localization and differentiation of the sounds of various aetiology on a small area (e.g. in auscultation of the heart), although the sounds themselves are slightly distorted by resonance. Sounds are usually more distinct with mediate auscultation.

During mediate auscultation with a solid stethoscope, vibrations are transmitted not only by the air inside the instrument but also through the solid part of the stethoscope and the temporal bone of the examiner (bone conduction). A simple stethoscope manufactured from wood, metal or plastics consists of a tube with a bell which is pressed against the chest wall, the other end of the stethoscope bearing a concave plate for the examiner's ear. Binaural stethoscopes are now widely used. These consist of two rubber tubes ending with self-retaining ear pieces connected to a single chest piece. The binaural stethoscope is more convenient, especially for auscultation of children and seriously-ill patients. Phonendoscopes differ from

simple stethoscopes in that they have a membrane covering the bell. Stethoscopes with electrical sound amplification were designed. They, however, were declined by most physicians because of difficulties in differentiation and interpretation of sounds which can be achieved by experience. Amplifiers that are now available do not ensure uniform amplification of all frequencies and this distorts the sounds.

A stethoscope is a closed acoustic system where air serves as a transmitting medium for sounds. Therefore, if the tube is clogged, or communicates with ambient air, auscultation becomes impossible. The skin against which the bell of the stethoscope is pressed acts as a membrane whose acoustic properties change under pressure: if the pressure on the skin increases higher frequencies are better transmitted, and vice versa. Excess pressure on the bell damps vibration of the underlying tissues. A large bell better transmits lower frequencies.

In order to decrease resonance (i.e. to lessen intensification of one tone in the combination of various tones) it is necessary that the ear and the chest piece were not very deep, while the internal cavity of the phonendoscope bell had a parabollic section; the length of a solid (one-piece) stethoscope should not exceed 12 cm. It is also desirable that the tubes of inelastic phonendoscope be as short as possible while the amount of air inside the system as small as possible.

The human ear perceives vibrations in the range from 16-20 to 20000 per second, i.e. from 16 to 20000 Hz; variations in frequency are differentiated better than in the sound intensity. The highest sensitivity of the ear is to sounds of 2000 Hz. The sensitivity decreases sharply with decreasing frequency. For example, it decreases to 50 per cent at 1000 Hz and to 0.9 per cent at 100 Hz. It should also be remembered that a weak sound is perceived with difficulty after a loud sound.

All auscultation sounds are noise, i.e. a mixture of sounds of various frequencies. Noise percepted during auscultation of the heart and lungs are mostly vibrations in the range from 20 to 600 Hz. Bronchial respiration produces sounds in the range of frequencies from 240 to 1000 Hz, friction sounds and cardiac murmurs from 75 to 500 Hz, the first heart sound from 28 to 150 Hz, of the gallop sound from 28 to 150 (commonly from 30 to 60 Hz) and of the third heart sound from 25 to 35 Hz (at the threshold of audibility). Phonocardiographic studies show that the lower limit of sound frequencies produced by the heart is to 5— 10 Hz, i.e. beyond audibility threshold of the human ear. Low frequency vibrations can be felt by Palpation, e.g. vibration of tissues in the precardial region which is known as cat's purr in mitral and aortal stenosis, vibrations produced by pleural friction and friction of the pericardium in dry pleurisy and pericarditis, etc.

Auscultation has remained an indispensable diagnostic technique for examining the heart, lungs and vessels, determining arterial pressure by Korotkoff's method, for diagnosing arteriovenous and intracranial aneurysms, and also in obstetrical practice. Auscultation is important for the study of the alimentary organs (intestinal murmurs, peritoneal friction) ai*d also of joints (friction of intra-articular surfaces of the epiphysis).

Auscultation techniques. Special rules should be followed during

Chapter 3. Methods of Clinical Examination

General Part

auscultation paying particular attention to conditions in which it is carried out. The first requirement is silence in the room and the absence of any extraneous sounds that might mask the sounds heard by the physician. The ambient temperature should provide comfort for the undressed patient. During auscultation the patient is either sitted or stands upright. If the patient is in grave condition he may remain lying in bed. During auscultation of the lungs of a lying patient, his chest is first auscultated on one side and then the patient is turned to the other side and auscultation is continued. The skin to which the bell of the phonendoscope is pressed should be hairless because hair produces additional friction which interferes with differentiation and interpretation of the sounds. When using a stethoscope its bell should be pressed firmly and uniformly to the patient's skin but the pressure should be moderate since excess pressure damps vibration of the skin to diminish the intensity of the sounds. The bell of the stethoscope should be held by the thumb and the forefinger. The posture of the patient should be varied in order to ensure better conditions for auscultation of each particular organ. For example, the diastolic sound in aortic incompetence is better heard with the patient in the sitting or standing position, while the diastolic sound in mitral stenosis, with a patient lying on his side (especially on his left side). The respiration of the patient should be regulated by the physician and in some cases the patient is asked to cough (e.g. rales in the lungs may disappear or change their properties after expectoration).

Many various stethoscopes and phonendoscopes are now produced by the medical industry but they differ mostly in design. It is important that the physician should use an instrument to which he got accustomed. An experienced physician will always feel it difficult to differentiate and interpret sounds if a new stethoscope is used for some reasons. This explains the necessity of sufficient theoretical knowledge on the part of the physician so that he might correctly interpret the heard sounds. Hence the necessity of constant training in auscultation. Only permanent use of this diagnostic technique will make it a useful tool of diagnosis.

|

|