Главная страница Случайная страница

Разделы сайта

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Debating societies

|

|

The Debating Societies that rapidly came into existence in 1780 London present an almost perfect example of the public sphere during the Enlightenment. Donna T Andrew provides four separate origins:

· Clubs of fifty or more men who, at the beginning of the 18th century, met in pubs to discuss religious issues and affairs of state.

· Mooting clubs, set up by law students to practice rhetoric.

· Spouting clubs, established to help actors train for theatrical roles.

· William Henley’s Oratory, which mixed outrageous sermons with even more absurd questions, like “Whether Scotland be anywhere in the world? ”[64]

In any event, popular debating societies began, in the late 1770s, to move into more “genteel”, or respectable rooms, a change which helped establish a new standard of sociability: “order, decency, and liberality”, in the words of the Religious Society of Old Portugal Street. Respectability was also encouraged by the higher admissions prices (ranging from 6d. to 3s.), which also contributed to the upkeep of the newer establishments. The backdrop to these developments was what Andrew calls “an explosion of interest in the theory and practice of public elocution”. The debating societies were commercial enterprises that responded to this demand, sometimes very successfully. Indeed, some societies welcomed from 800 to 1200 spectators a night.[66] These societies discussed an extremely wide range of topics. One broad area was women: societies debated over “male and female qualities”, courtship, marriage, and the role of women in the public sphere. Societies also discussed political issues, varying from recent events to “the nature and limits of political authority”, and the nature of suffrage. Debates on religion rounded out the subject matter. It is important to note, however, that the critical subject matter of these debates did not necessarily translate into opposition to the government. In other words, the results of the debate quite frequently upheld the status quo.

From a historical standpoint, one of the most important features of the debating society was their openness to the public; women attended and even participated in almost every debating society, which were likewise open to all classes providing they could pay the entrance fee. Once inside, spectators were able to participate in a largely egalitarian form of sociability that helped spread “Enlightening ideas”.

Classicism, in the arts, refers generally to a high regard for classical antiquity, as setting standards for taste which the classicists seek to emulate. The art of classicism typically seeks to be formal and restrained: of the Discobolus Sir Kenneth Clark observed, " if we object to his restraint and compression we are simply objecting to the classicism of classic art. A violent emphasis or a sudden acceleration of rhythmic movement would have destroyed those qualities of balance and completeness through which it retained until the present century its position of authority in the restricted repertoire of visual images." [1] Classicism, as Clark noted, implies a canon of widely accepted ideal forms, whether in the Western canon that he was examining in The Nude (1956), or the Chinese classics.

Classicism is a force which is often present in post-medieval European and European influenced traditions; however, some periods felt themselves more connected to the classical ideals than others, particularly the Age of Reason, the Age of Enlightenment, and some classicizing movements in Modernism.

Classicism is a specific genre of philosophy, expressing itself in literature, architecture, art, and music, which has Ancient Greek and Roman sources and an emphasis on society. It was particularly expressed in the Enlightenment, and the Age of Reason.

Classicism first made an appearance as such during the Italian renaissance when the fall of Byzantium and rising trade with the Islamic cultures brought a flood of knowledge about, and from, the antiquity of Europe. Until that time the identification with antiquity had been seen as a continuous history of Christendom from the conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine I. Renaissance classicism introduced a host of elements into European culture, including the application of mathematics and empiricism into art, humanism, literary and depictive realism, and formalism. Importantly it also introduced Polytheism, or " paganism", and the juxtaposition of ancient and modern.

The classicism of the Renaissance lead to, and gave way to, a different sense of what was " classical" in the 16th and 17th centuries. In this period classicism took on more overtly structural overtones of orderliness, predictability, the use of geometry and grids, the importance of rigorous discipline and pedagogy, as well as the formation of schools of art and music. The court of Louis XIV was seen as the center of this form of classicism, with its references to the gods of Olympus as a symbolic prop for absolutism, its adherence to axiomatic and deductive reasoning, and its love of order and predictability. This period sought the revival of classical art forms, including Greek drama and music. Opera, in its modern European form, had its roots in attempts to recreate the combination of singing and dancing with theatre thought to be the Greek norm. Examples of this appeal to classicism included Dante, Petrarch, and Shakespeare in poetry and theatre. Tudor drama, in particular, modeled itself after classical ideals and divided works into Tragedy and Comedy. Studying ancient Greek became regarded as essential for a well-rounded education in the liberal arts.

Classicist door in Olomouc, The Czech Republic

The Renaissance also explicitly returned to architectural models and techniques associated with Greek and Roman antiquity, including the golden rectangle as a key proportion for buildings, the classical orders of columns, as well as a host of ornament and detail associated with Greek and Roman architecture. They also began reviving plastic arts such as bronze casting for sculpture, and used the classical naturalism as the foundation of drawing, painting and sculpture.

The Age of the Enlightenment identified itself with a vision of antiquity which, while continuous with the classicism of the previous century, was shaken by the physics of Sir Isaac Newton, the improvements in machinery and measurement, and a sense of liberation which they saw as being present in the Greek civilization, particularly in its struggles against the Persian Empire. The ornate, organic, and complexly integrated forms of the baroque were to give way to a series of movements that regarded themselves expressly as " classical" or " neo-classical", or would rapidly be labelled as such. For example the painting of Jacques-Louis David which was seen as an attempt to return to formal balance, clarity, manliness, and vigor in art.

The 19th century saw the classical age as being the precursor of academicism, including such movements as uniformitarianism in the sciences, and the creation of rigorous categories in artistic fields. Various movements of the romantic period saw themselves as classical revolts against a prevailing trend of emotionalism and irregularity, for example the Pre-Raphaelites. By this point classicism was old enough that previous classical movements received revivals; for example, the Renaissance was seen as a means to combine the organic medieval with the orderly classical. The 19th century continued or extended many classical programs in the sciences, most notably the Newtonian program to account for the movement of energy between bodies by means of exchange of mechanical and thermal energy.

The 20th century saw a number of changes in the arts and sciences. Classicism was used both by those who rejected, or saw as temporary, transfigurations in the political, scientific, and social world and by those who embraced the changes as a means to overthrow the perceived weight of the 19th century. Thus, both pre-20th century disciplines were labelled " classical" and modern movements in art which saw themselves as aligned with light, space, sparseness of texture, and formal coherence.

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes both a set of cultural tendencies and an array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2][3][3] The term encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the " traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an emerging fully industrialized world.

Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking, and also that of the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator.[4][5] This is not to say that all modernists or modernist movements rejected either religion or all aspects of Enlightenment thought, rather that modernism can be viewed as a questioning of the axioms of the previous age.

A salient characteristic of modernism is self-consciousness. This often led to experiments with form, and work that draws attention to the processes and materials used (and to the further tendency of abstraction).[6] The poet Ezra Pound's paradigmatic injunction was to " Make it new! " Whether or not the " making new" of the modernists constituted a new historical epoch is up for debate. Philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno warns us:

" Modernity is a qualitative, not a chronological, category. Just as it cannot be reduced to abstract form, with equal necessity it must turn its back on conventional surface coherence, the appearance of harmony, the order corroborated merely by replication." [7]

Adorno would have us understand modernity as the rejection of the false rationality, harmony, and coherence of Enlightenment thinking, art, and music. But the past proves sticky. Pound's general imperative to make new, and Adorno's exhortation to challenge false coherence and harmony, faces T. S. Eliot's emphasis on the relation of the artist to tradition. Eliot wrote:

" [W]e shall often find that not only the best, but the most individual parts of [a poet's] work, may be those in which the dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously." [8]

Literary scholar Peter Childs sums up the complexity:

" There were paradoxical if not opposed trends towards revolutionary and reactionary positions, fear of the new and delight at the disappearance of the old, nihilism and fanatical enthusiasm, creativity and despair." [9]

These oppositions are inherent to modernism: it is in its broadest cultural sense the assessment of the past as different to the modern age, the recognition that the world was becoming more complex, and that the old " final authorities" (God, government, science, and reason) were subject to intense critical scrutiny.

Surrealism was known to the public as the most extreme among the forms of modernism.[10] Current interpretations of modernism vary. Some[ who? ] divide 20th century reaction into modernism and postmodernism, whereas others[ who? ] see them as two aspects of the same movemen

The first half of the 19th century for Europe was marked by a number of wars and revolutions, which contributed to an aesthetic " turning away" from the realities of political and social fragmentation, and so facilitated a trend towards Romanticism.[ citation needed ] Romanticism had been a revolt against the values of the Industrial Revolution and bourgeois conservative values, [2][3][13] putting emphasis on individual subjective experience, the sublime, the supremacy of " Nature" as a subject for art, revolutionary or radical extensions of expression, and individual liberty.

A Realist portrait of Otto von Bismarck.

By mid-century, however, a synthesis of the ideas of Romanticism with stable governing forms had emerged, [ citation needed ] partly in reaction to the failed Romantic and democratic Revolutions of 1848. It was exemplified by Otto von Bismarck's Realpolitik and by " practical" philosophical ideas such as positivism.[ citation needed ] This stabilizing synthesis, the Realist political and aesthetic ideology, was called by various names—in Great Britain it is designated the " Victorian era" — and was rooted in the idea that reality dominates over subjective impressions. Central to this synthesis were common assumptions and institutional frames of reference, including the religious norms found in Christianity, scientific norms found in classical physics and doctrines that asserted that the depiction of external reality from an objective standpoint was not only possible but desirable. Cultural critics and historians label this set of doctrines realism, though this term is not universal. In philosophy, the rationalist, materialist and positivist movements established a primacy of reason and system.

Against the current ran a series of ideas, some of them direct continuations of Romantic schools of thought. Notable were the agrarian and revivalist movements in plastic arts and poetry (e.g. the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the philosopher John Ruskin). Rationalism also drew responses from the anti-rationalists in philosophy. In particular, Hegel's dialectic view of civilization and history drew responses from Friedrich Nietzsche and Sø ren Kierkegaard, who were major influences on existentialism. All of these separate reactions together began to be seen as offering a challenge to any comfortable ideas of certainty derived by civilization, history, or pure reason.

From the 1870s onward, the ideas that history and civilization were inherently progressive and that progress was always good came under increasing attack. Writers Wagner and Ibsen had been reviled for their own critiques of contemporary civilization and for their warnings that accelerating " progress" would lead to the creation of individuals detached from social values and isolated from their fellow men. Arguments arose that the values of the artist and those of society were not merely different, but that Society was antithetical to Progress, and could not move forward in its present form. Philosophers called into question the previous optimism. A generation earlier, in the 1840s the work of Schopenhauer was labelled " pessimistic" for its idea of the " negation of the will", an idea that would be both rejected and incorporated by later thinkers such as Nietzsche.

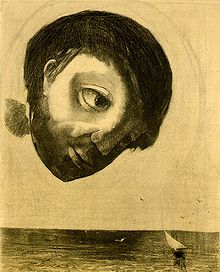

Odilon Redon, Guardian Spirit of the Waters, 1878, charcoal on paper, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Two of the most significant thinkers of the 1840-70 period were, in biology, Charles Darwin, and in political science, Karl Marx. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection undermined the religious certainty of the general public, and the sense of human uniqueness of the intelligentsia. The notion that human beings were driven by the same impulses as " lower animals" proved to be difficult to reconcile with the idea of an ennobling spirituality. Karl Marx, whose disdain for religions was far greater than Darwin's, argued there were fundamental contradictions within the capitalist system—and that the workers were anything but free. Both thinkers would spawn defenders and schools of thought that would become decisive in establishing modernism.[ citation needed ]

Historians have suggested various dates as starting points for modernism. William Everdell has argued that modernism began with Richard Dedekind's division of the real number line in 1872 and Boltzmann's statistical thermodynamics in 1874. Clement Greenberg called Immanuel Kant " the first real Modernist", [14] but also wrote, " What can be safely called Modernism emerged in the middle of the last century—and rather locally, in France, with Baudelaire in literature and Manet in painting, and perhaps with Flaubert, too, in prose fiction. (It was a while later, and not so locally, that Modernism appeared in music and architecture)." [15] At first, modernism was called the " avant-garde", and the term remained to describe movements which identify themselves as attempting to overthrow some aspect of tradition or the status quo.[16][ page needed ]

Separately, in the arts and letters, two ideas originating in France would have particular impact. The first was impressionism, a school of painting that initially focused on work done, not in studios, but outdoors (en plein air). Impressionist paintings demonstrated that human beings do not see objects, but instead see light itself, a light that is neither constant nor steady, but momentarily changing. The school gathered adherents despite internal divisions among its leading practitioners, and became increasingly influential. Initially rejected from the most important commercial show of the time, the government-sponsored Paris Salon, the Impressionists organized yearly group exhibitions in commercial venues during the 1870s and 1880s, timing them to coincide with the official Salon. A significant event of 1863 was the Salon des Refusé s, created by Emperor Napoleon III to display all of the paintings rejected by the Paris Salon. While most were in standard styles, but by inferior artists, the work of Manet attracted tremendous attention, and opened commercial doors to the movement.

The second school was symbolism, marked by a belief that language is expressly symbolic in its nature and a portrayal of patriotism, and that poetry and writing should follow connections that the sheer sound and texture of the words create. The poet Sté phane Mallarmé would be of particular importance to what would occur afterwards.

At the same time social, political, and economic forces were at work that would become the basis to argue for a radically different kind of art and thinking. Chief among these was steam-powered industrialization, which produced buildings that combined art and engineering in new industrial materials such as cast iron and steel to produce railroad bridges and glass-and-iron train sheds—or the Eiffel Tower, which broke all previous limitations on how tall man-made objects could be—and at the same time offered a radically different environment in urban life.

The miseries of industrial urbanism and the possibilities created by scientific examination of subjects brought changes that would shake a European civilization which had, in the 18th century, regarded itself as having a continuous and progressive line of development from the Renaissance. With the telegraph's harnessing of a new power (1837–47), offering instant communication at a distance, together with the telephone (1876), the photograph (1839) and the phonograph (1877), the experience of time itself was altered.

Most of the intellectual disciplines we know today began organizing, defining themselves and holding formal conferences in the period 1885-1900. Many of these disciplines, sciences like Mathematics, Physics, Economics and Biology, and arts such as Literature, Dance and Architecture) specifically refer to their 20th-century forms as " modern, " while Physics, Economics, Dance and Architecture go on to refer to their pre-20th-century forms as " classical." This distinction indicates the scope of the changes that occurred across a wide range of scientific and cultural pursuits during the period.

|

|